I am the books I have read. I am the books I have written.

Immaginare l'Antico

Hardback, 30 x 24 cm, 160 pages, 120 color ill.

(2025)

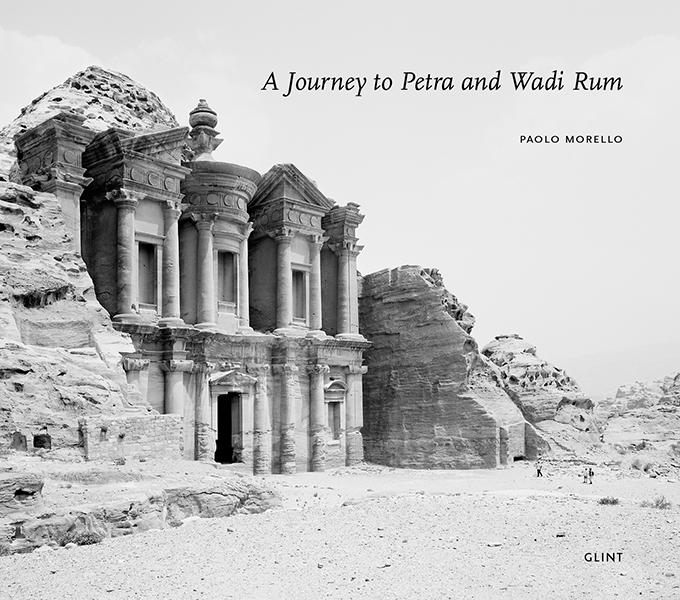

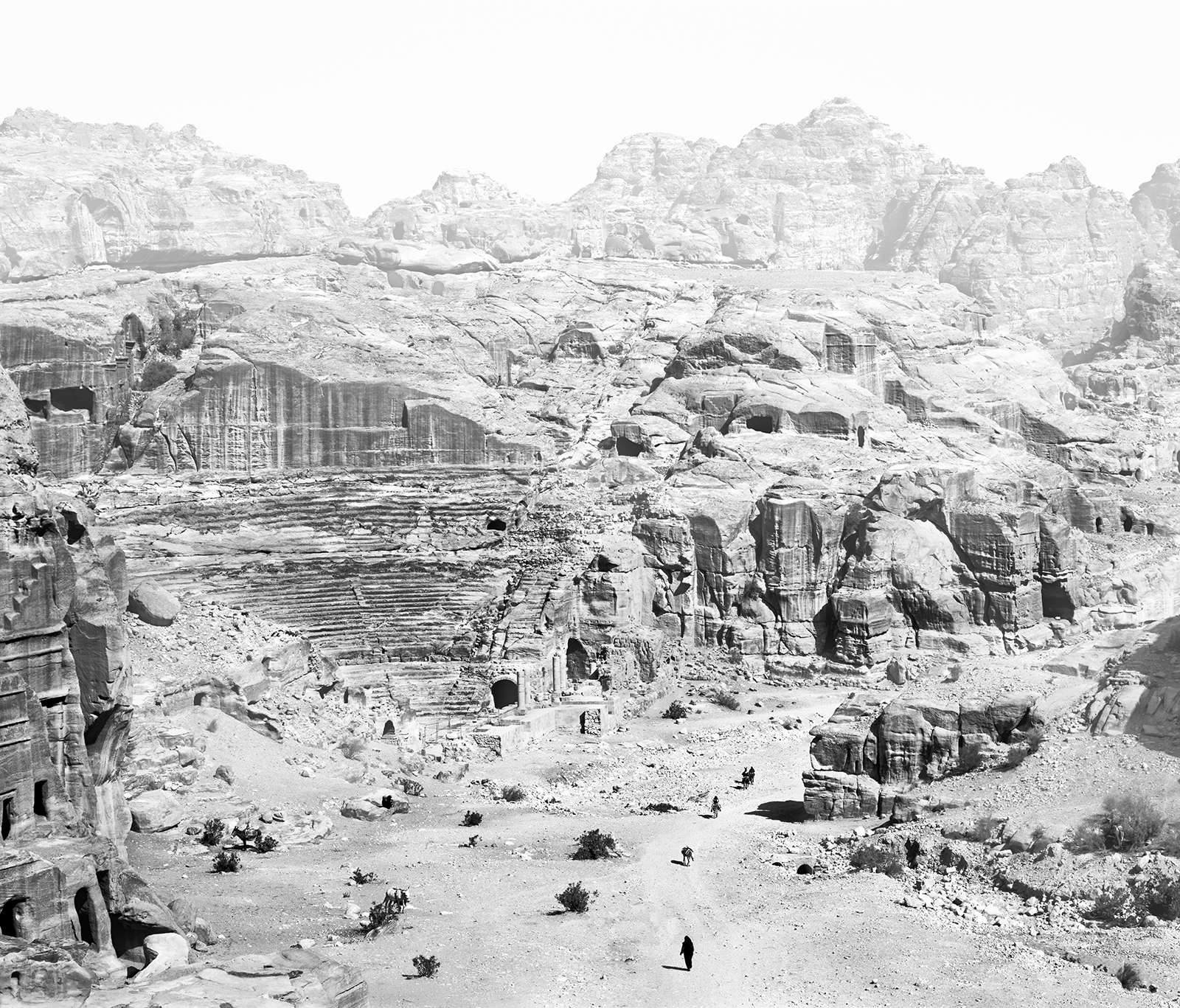

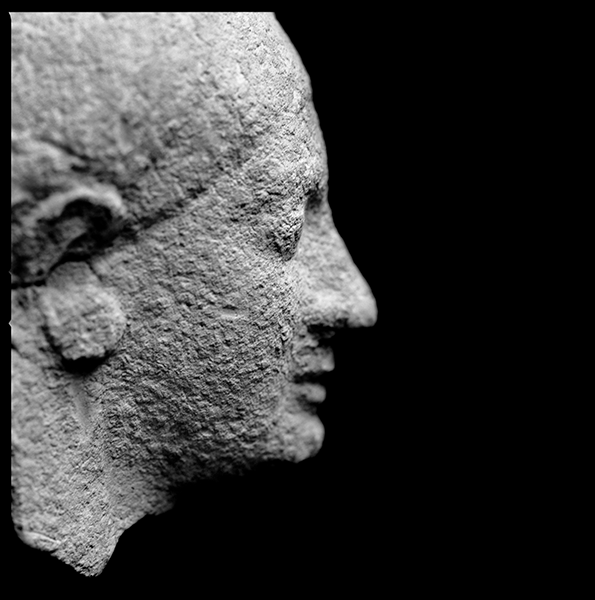

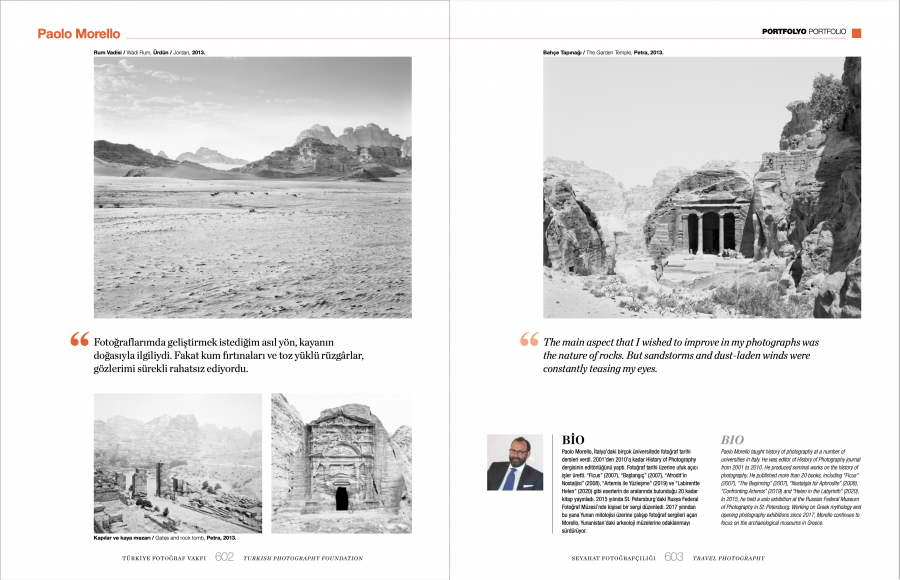

A Journey to Petra and Wadi Rum

Hardback, 30 x 24 cm, 96 pages, 76 tritone plates

out of stock

The oldest settlements in the area of Petra were inhabited by the Edomites – who were mentioned in the Book of Exodus – between the end of the VIII century and the beginning of the VII century BC. The town flourished a little later on thanks to the Nabataeans, an Arab nomadic tribe. In the…

Read moreThe oldest settlements in the area of Petra were inhabited by the Edomites – who were mentioned in the Book of Exodus – between the end of the VIII century and the beginning of the VII century BC. The town flourished a little later on thanks to the Nabataeans, an Arab nomadic tribe. In the first half of the II century BC the Nabataeans gave life to their kingdom, establishing in Petra their capital. Its ascent was mainly due to three different factors: the orography, which made it unconquerable, the abundance of water, and, most of all, the location. For several centuries Petra was the crossroads of the caravan routes from Aqaba and Yemen to Damascus and to Constantinople, which is to say, to all of the trade routes leading to a variety of goods – spices, incense, perfumes, and tar – from India to the Mediterranean countries and from Egypt to Persia.

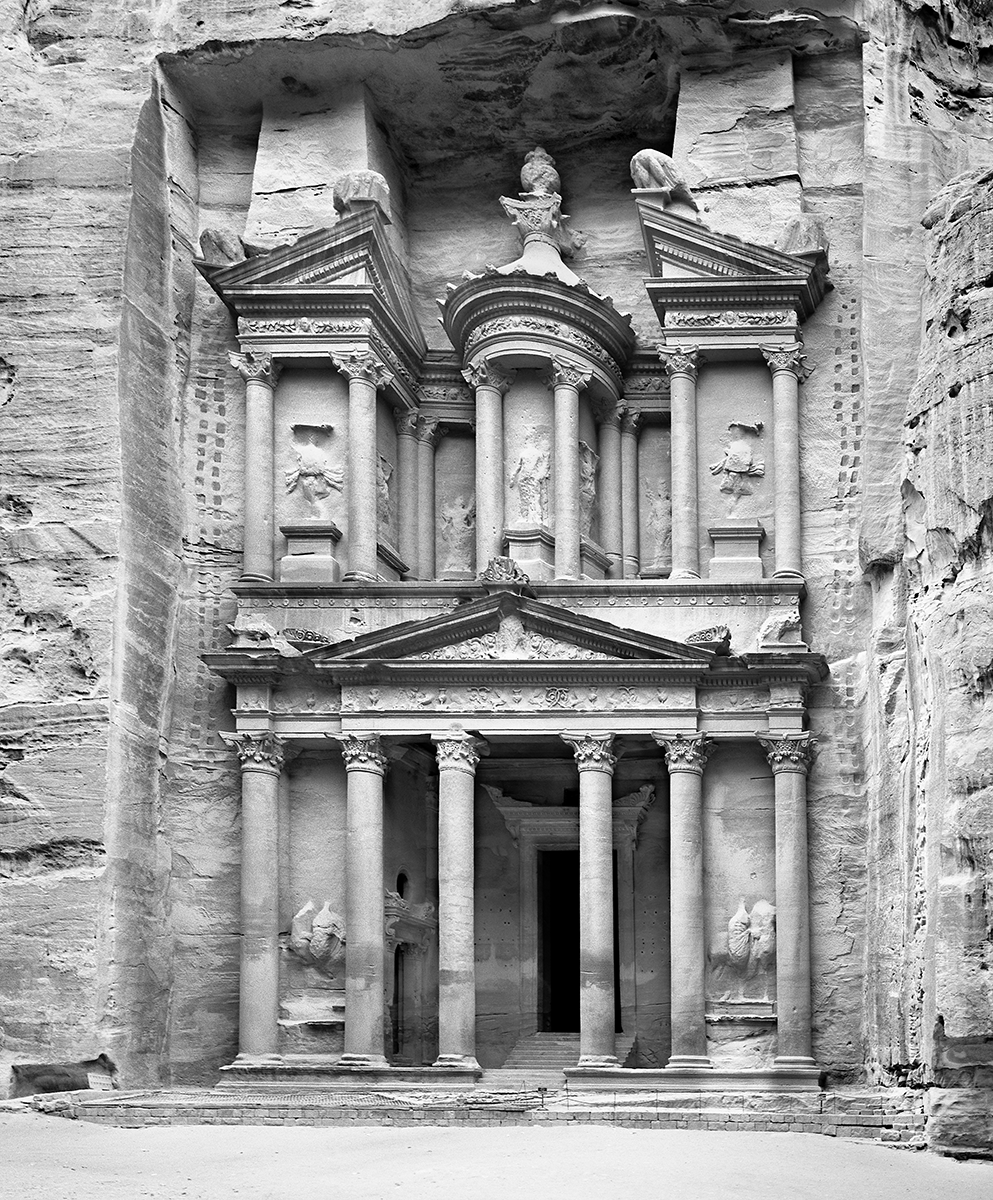

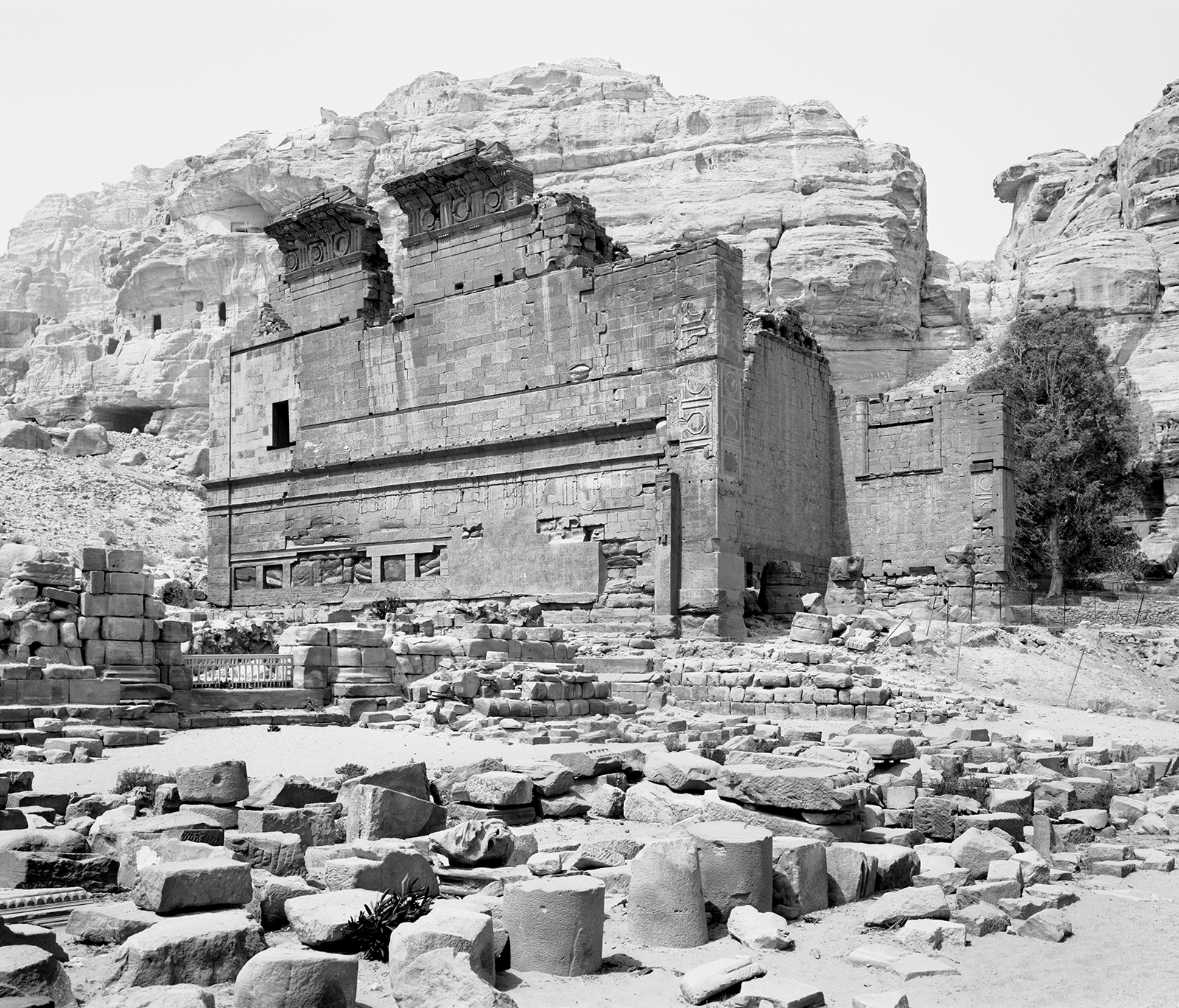

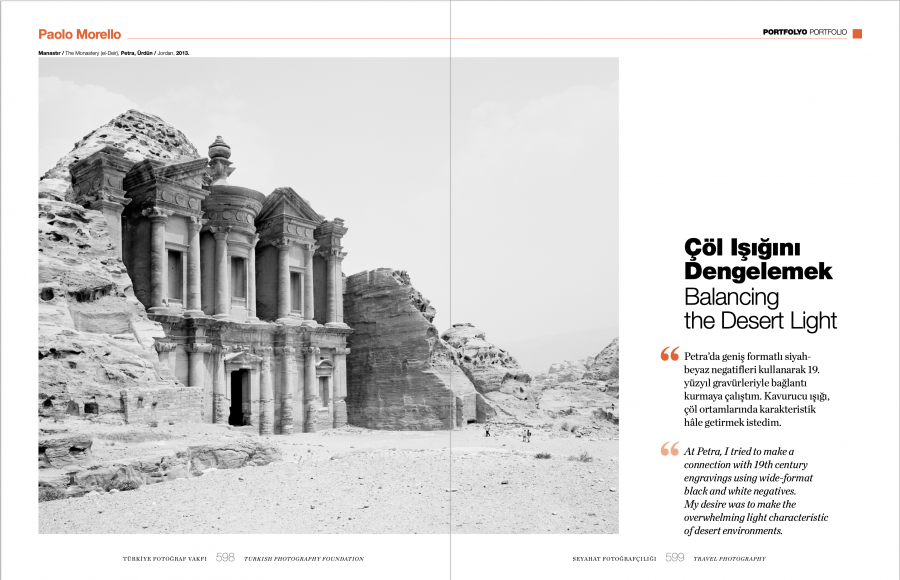

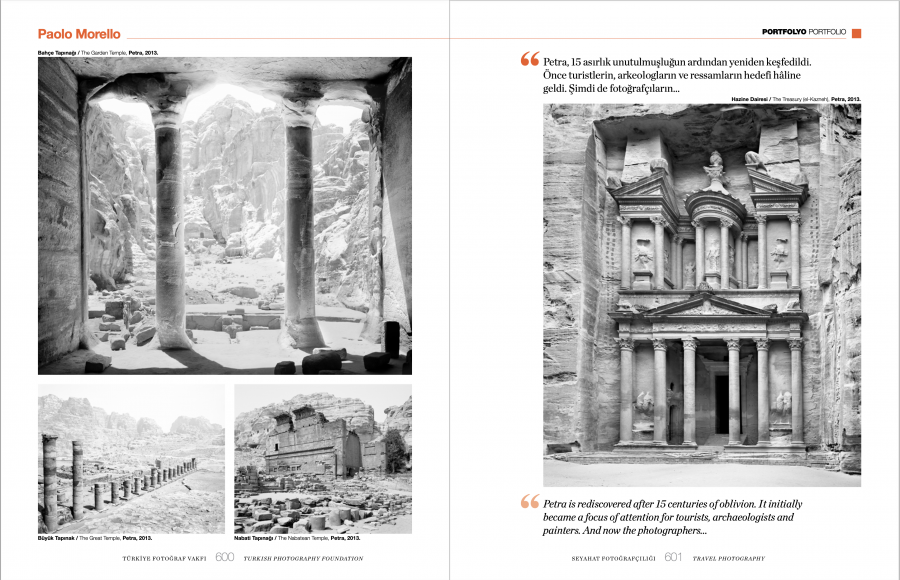

The first king of the Nabataeans of whom we have recorded evidence was ‘Ubayda I (known also as Obodas I), who ruled from 96 BC to 85 BC. After his death, he was worshiped as a god, and the most sumptuous grave in Petra was very likely dedicated to him, the so called al-Deir (the Monastery). Around 80 BC, the Nabataeans conquered the Seleucid territories, extending their domain northward as far as the Euphrates river and Palmyra. The son of ‘Ubayda I, al-Harith III (Areta III), expanded their kingdom further, all the way to Damascus. The other famous grave in Petra, al-Khazneh (the Treasury), which owes its name to the mistaken belief that the treasure of an Egyptian Pharaoh was hidden in it, is most likely dedicated to al-Harith III. Al-Harith’s greatest success was the agreement he negotiated with the Romans: by paying a huge toll in silver, the Nabataean kingdom ensured its substantial independence. Petra grew in power and wealth from 9 BC to 40 AD under king al-Harith IV, when its population reached about 30,000 people. Toward the end of the I century AD, the Romans shifted their trade routes to Egypt and along the Nile river; new towns became pivotal along the caravan routes, such as Bosra and Palmyra in Syria. In 106 AD the Nabataean kingdom was peacefully taken over by Rome. Bosra became the new capital of the Roman province called Arabia Petræa and from then on, Petra’s slow decline began.

After many centuries of oblivion, Petra was rediscovered in 1812 thanks to the Swiss explorer, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. Born in Lausanne in 1784, forced to leave Switzerland to go to Germany and then to Great Britain, in 1809 he was employed by the African Association as a member of an expedition whose objective was to discover the source of the Niger river. For this reason, he spent time in Cambridge, studying medicine, surgery, chemistry, astronomy, mineralogy, Arabic, and training himself to endure long walks and rigid fasts. In order to improve his knowledge of Arabic language and culture he was sent to the Middle East. In Aleppo, in Syria, where he settled, he changed his identity, took the name of Sheikh Ibrahim ibn Abdallah, and learnt to dress like a native, pretending to be an Hindustan merchant. His knowledge of the Arabic language was so fluent that he was able to translate Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. During his stay in Syria, he explored the region and its archaeological sites thoroughly – going to Damascus, to Baghdad, but also to Palmyra, and to Ba’albek in Lebanon. He wrote detailed reports in his daybooks about these travels, which were often very adventurous, and they were published after his death. He also reported about them in the letters he sent regularly to the African Association in London. In the summer of 1812 Burckhardt decided to go to Cairo along the Kings’ Road as far as Aqaba, heading to Timbuktu and to the source of the Niger river. With an excuse he convinced his guide to take him to Wadi Musa, a valley that the Bedouins guarded jealously as a secret. «It appears very probable that the ruins in Wadi Musa are those of the ancient Petra – he wrote in his journal – […]. At least I am persuaded, from all the information I procured, that there is no other ruin between the extremties of the Red Sea and the Dead Sea of sufficient importance to answer to that city. Whether or not I have discovered the remains of the Arabia Petræa, I leave to the decision of Greek scholars […]». (Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. Description of a Journey from Damascus through the Mountains of Arabia Petræa and the Desert El Ty, to Cairo; in the Summer of 1812, London 1822).

Burckhardt was only twenty-eight when he rediscovered Petra. He died five years later, in 1817. The posthumous publication of his travel journals generated great interest and other travellers retraced his footsteps in the years to come. But at that time, Petra was extremely difficult to reach: the valley was off the ordinary routes taken by the archaeologists and artists who went to the Middle East and visitors were very likely to be robbed by the natives. It is therefore worth mentioning the journey of two young French men, Léon de Laborde and Louis Linant de Bellefonds, who reached Petra in 1828. They made a large number of sketches, which were widely circulated upon their return home, giving the Western public the first pictorial representations of the monuments of the Nabataean town. In particular, the book published by Léon de Laborde in 1836, Journey through Arabia Petræa to Mount Sinai, and the Excavated City of Petra, the Edom of the Prophecies, became a source of inspiration for David Roberts, a Sottish painter who in March 1839 travelled to Petra and to the Middle East with the precise purpose of painting a series of landscapes to sell on his return home. Thus Petra’s image began to take shape. Photographs, however, are much rarer evidence. One of the first known photographers was Louis Vignes, who arrived in Petra in 1864 with an expedition organized by the duke de Luynes, a collector, archaeologist and photographer himself, who between 1866 and 1874 would publish his account in a book illustrated with sixty-four photo-etchings and lithographs taken from photographs (Voyage of Exploration to the Dead Sea, and on the Left Bank of the Jordan, Paris 1874).

In 1985, Petra was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since then, it has been the subject of an infinite quantity of pictures, which unfailingly represent always the same views, from the same perspective, without contributing much to a profound understanding of the place. Like many other touristic attractions, Petra today coincides with its image. The emotion of the exploration and the discovery, which one can feel pulsating in XIXth-century travellers’ journals, has vanished; it has been substituted, in the pictures taken by modern tourists, by an automatic process of confirmation of something already known, by the simple repetition of stereotyped images which have already been seen thousands of times. The photographs here on display strive to shatter these clichés. By avoiding the postcard effects of the ‘Rose-Red-City’ they hope to rebuild a dialogue with the XIXth-century travellers’ perspective, while illuminating the relationship between nature, rocks and architecture.

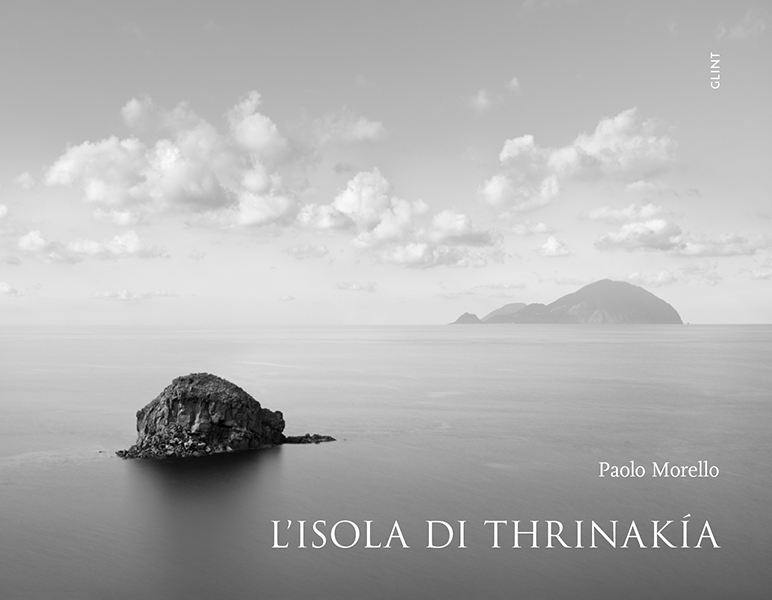

Read lessL'isola di Thrinakìa

Hardback, 30 x 24 cm, 64 pages, 42 tritone plates

2022

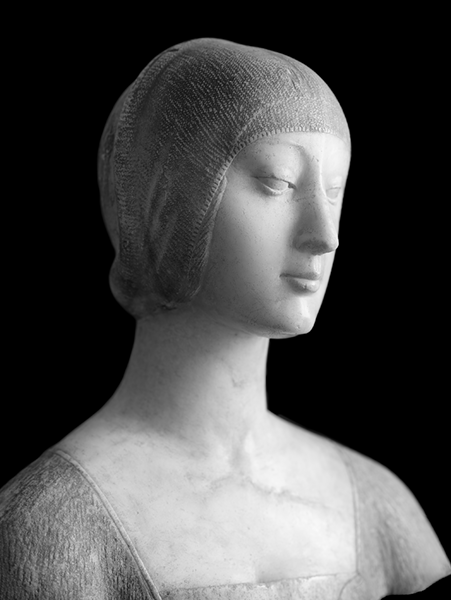

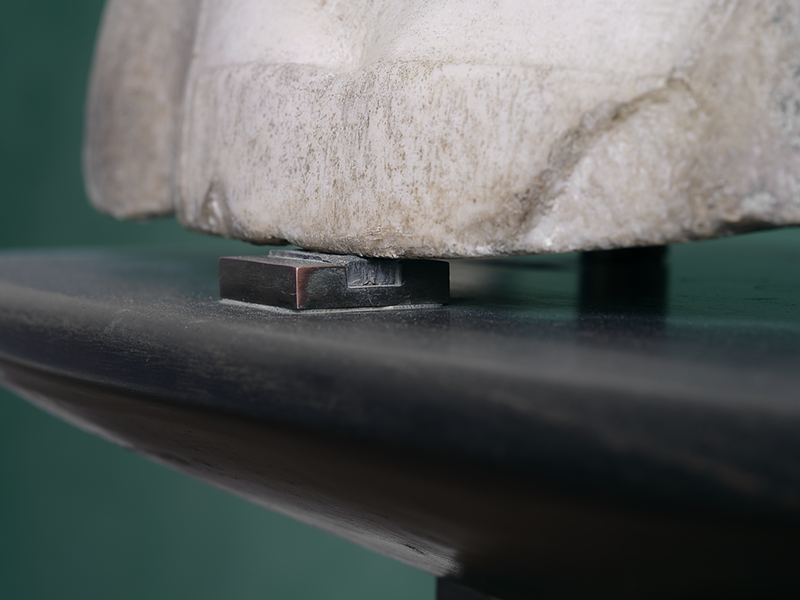

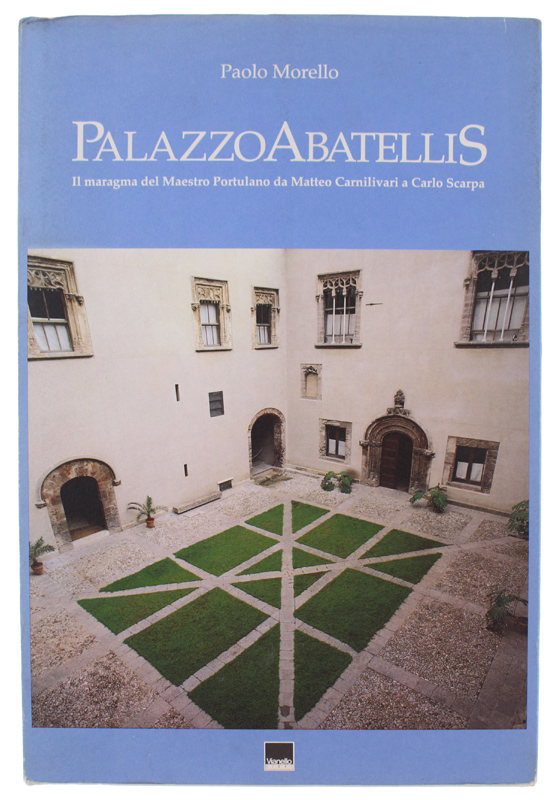

Palazzo Abatellis

33 x 43 cm, Hardback, English and Italian edition

(2025)

Thirty-five years have passed since Carlo Scarpa’s drawings for the installation of the Museum of Palazzo Abatellis, in Palermo, came back to light, restoring the fame due to a work which, up to that point, had occupied little more than one known in the monographs dedicated to the Venetian genius. Together with the drawings, the…

Read moreThirty-five years have passed since Carlo Scarpa’s drawings for the installation of the Museum of Palazzo Abatellis, in Palermo, came back to light, restoring the fame due to a work which, up to that point, had occupied little more than one known in the monographs dedicated to the Venetian genius. Together with the drawings, the correspondence between Scarpa and Giorgio Vigni, the superintendent who wanted him in Sicily, resurfaced. A precious collection of letters to reconstruct the progression of the works and the genesis of some rooms, such as that of the Triumph of Death.

Trentacinque anni sono trascorsi da quando i disegni di Carlo Scarpa per l’allestimento del Museo di palazzo Abatellis, a Palermo, sono tornati alla luce, restituendo la fama dovuta ad un’opera che, fino a quel punto, aveva occupato poco più di una nota nelle monografie dedicate al genio veneziano. Insieme con i disegni, riemerse il carteggio intercorso tra Scarpa e Giorgio Vigni, il soprintendente che lo volle in Sicilia. Un epistolario prezioso per ricostruire la progressione dei lavori e la genesi di alcune sale, come quella del Trionfo della Morte.

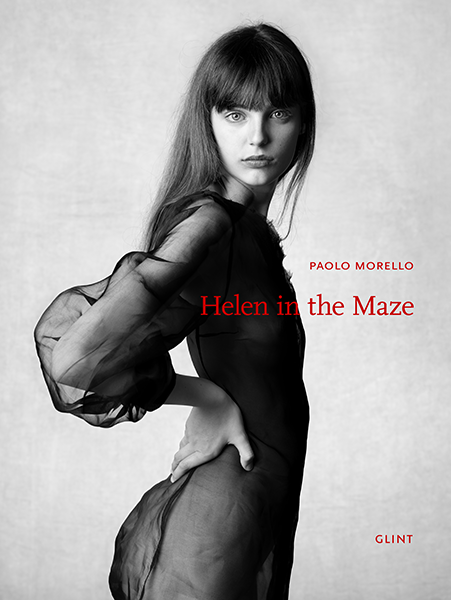

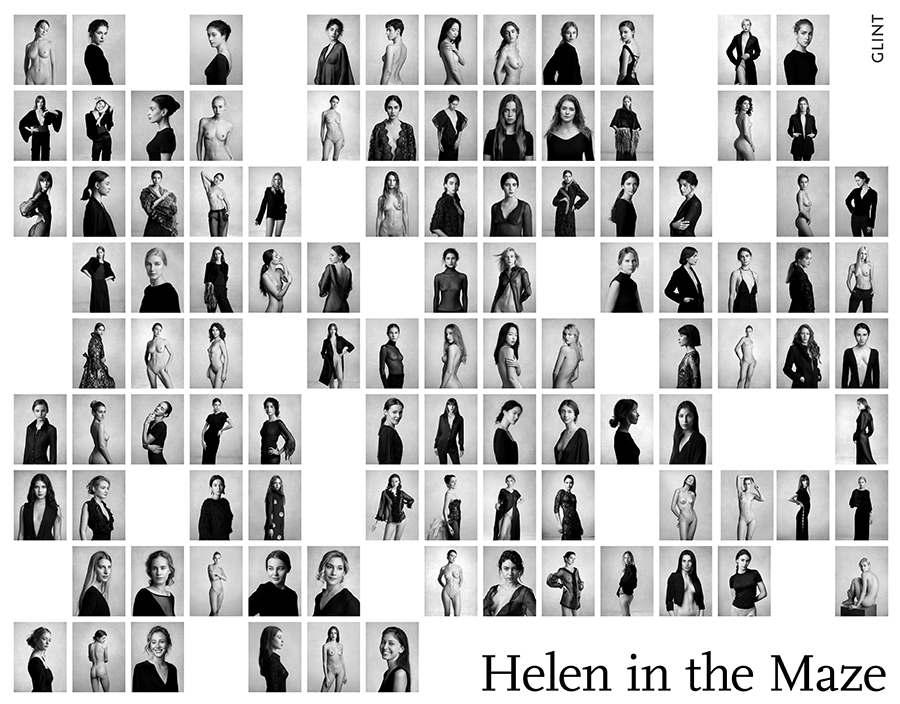

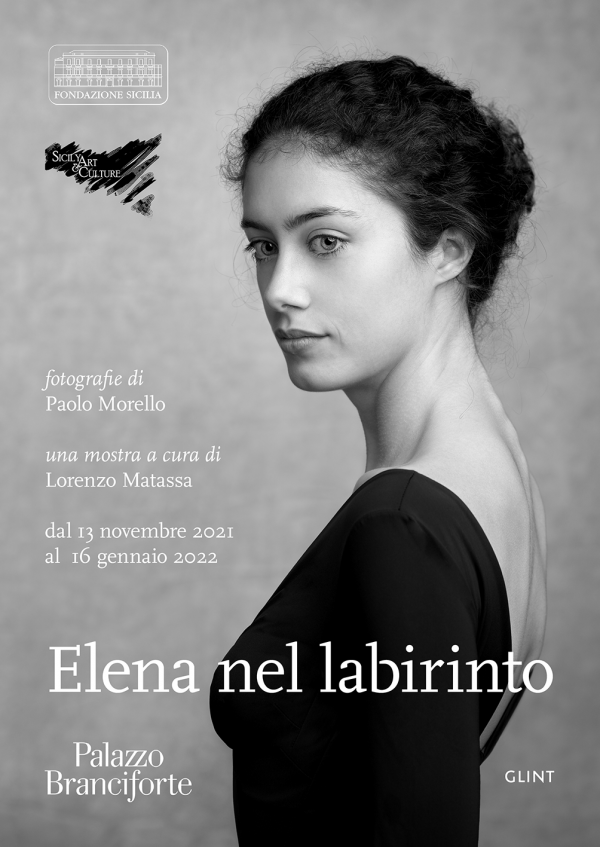

Read lessHELEN IN THE MAZE

Hardback, 24 x 31 cm, 112 pages, 90 tritone plates with varnish

2024

“For this new chapter of my research, the initial theme was loving one’s own image more than oneself. Where other than Milan, a global fashion capital, does a place exist that is better suited for reflecting on a topic which is actually very old? – that is, the rift between being and appearance, between image…

Read more“For this new chapter of my research, the initial theme was loving one’s own image more than oneself. Where other than Milan, a global fashion capital, does a place exist that is better suited for reflecting on a topic which is actually very old? – that is, the rift between being and appearance, between image and identity, a question first posed by Parmenides in about 500 bce, but still of great topical interest today. Our lives are steeped in images and we are constantly besieged by images. We love our image, and we cultivate it and attend to it. We delegate to it the task of representing us. We have made it a cult object. Ours is a civilisation of images, we are told. Image conditions what we buy, and to a great extent determines our frustrations and our happiness. Compulsively, we send images to friends, and to recipients we do not even know; social networks reveal the most intimate moments of our daily lives, in deference to the principle that nothing exists unless it is not communicated. This obsessive need for self-representation, which is such a distinctive part of our age, is radically redefining the functions of the portrait. The photographic portrait is the symbolic place where the terms image and identity collide. Every portrait is a projection onto photosensitive paper of an inextricable bundle of expectations, urgent needs, ambitions, challenges, and fears, all in an endless game of mirrors, pitting what I think I know of myself against what I would like others to see, what I discover unexpectedly against what I dream of being. A portrait is an instrument of introspection, of growth, of examination. An opportunity to enhance one’s self-awareness Every portrait questions its own subject. What pleasure, or apprehension, curiosity or wonder, what need to share, or show o€, led you to pose? The need to vanquish time, to leave an enduring trace of your likeness? To indelibly set down your real appearance, or what you thought, or would always have liked to be? Every portrait asks a crucial question of its subject, and constantly re-poses it: who am I?”.

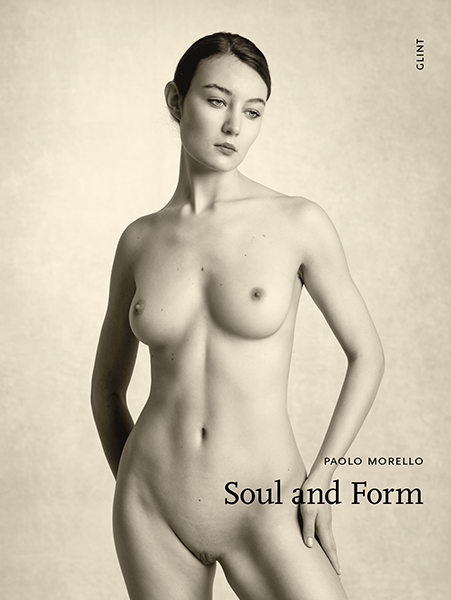

Read lessSOUL AND FORM

Hardback, 24 x 31 cm, 112 pages, 108 color plates with varnish - English edition - euro 50,00

2024

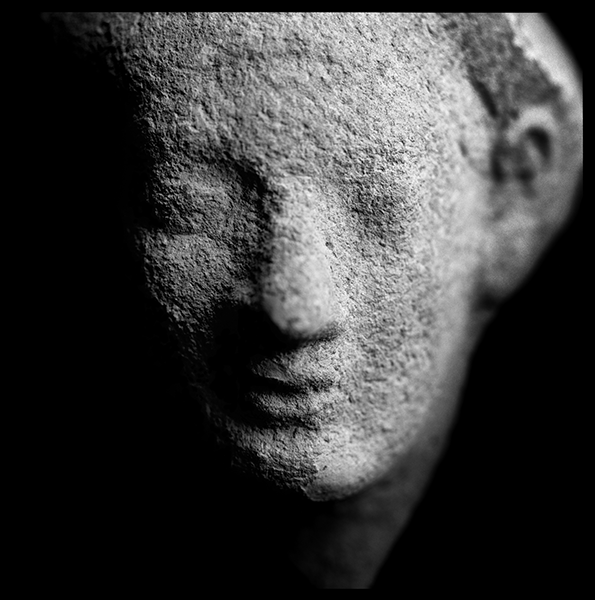

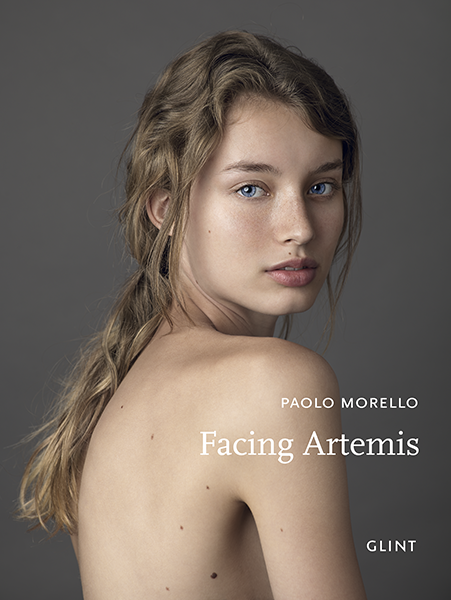

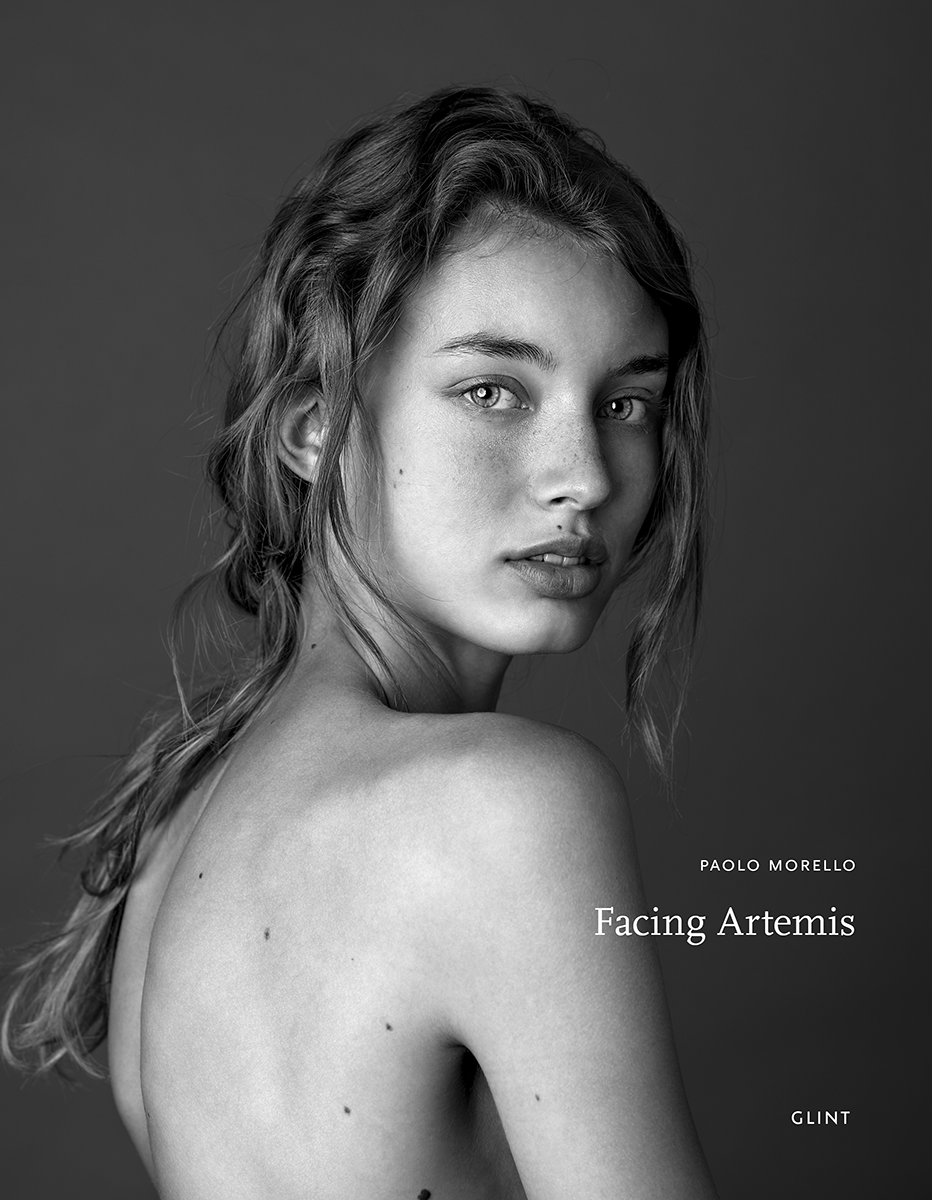

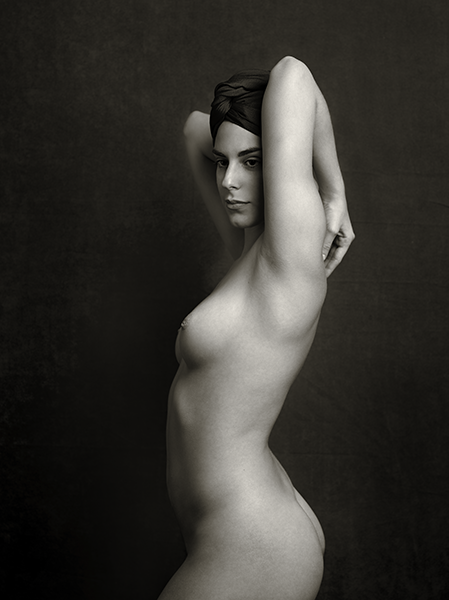

Facing Artemis

Hardback, 24 x 31 cm, 112 pages, 94 plates with varnish - English edition - euro 65,00

2018

“Muse, sing of Artemis, sister of the Far-shooter, the virgin who delights in arrows, who was fostered with Apollo”: thus opens the first of the two Homeric Hymns dedicated to the goddess. She excels “supreme among the immortals both in thought and in deed”, continues the second Hymn: Artemis, “whose shafts are of gold, who…

Read more“Muse, sing of Artemis, sister of the Far-shooter, the virgin who delights in arrows, who was fostered with Apollo”: thus opens the first of the two Homeric Hymns dedicated to the goddess. She excels “supreme among the immortals both in thought and in deed”, continues the second Hymn: Artemis, “whose shafts are of gold, who cheers on the hounds, the pure maiden, shooter of stags, who delights in archery, own sister to Apollo with the golden sword. Over the shadowy hills and windy peaks she draws her golden bow, rejoicing in the chase, and sends out grievous shafts. The tops of the high mountains tremble and the tangled wood echoes awesomely with the outcry of beasts: earthquakes and the sea also where fishes shoal. But the goddess with a bold heart turns every way destroying the race of wild beasts”. Four centuries later, during the first half of the third century before Christ, Callimachus imagined her as an adolescent, on the lap of Zeus. She makes a request of him: “Give me to keep my maidenhood, Father, forever: and give me to be of many names, that Phoebus may not vie with me. And give me arrows and a bow […] But give me to be Bringer of Light and give me to gird me in a tunic with embroidered border reaching to the knee, that I may slay wild beasts. And give me sixty daughters of Oceanus for my choir – all nine years old, all maidens yet ungirdled; and give me for handmaidens twenty nymphs of Amnisus who shall tend well my buskins, and, when I shoot no more at lynx or stag, shall tend my swift hounds. And give to me all mountains; and for city, assign me any, even whatsoever thou wilt: for seldom is it that Artemis goes down to the town. On the mountains will I dwell and the cities of men I will visit only when women vexed by the sharp pang of childbirth call me to their aid”.

Of the many stories of Artemis, we shall address only one on this occasion: her deadly, fortuitous encounter with Actaeon. It forms a myth that already enjoyed widespread popularity in ancient times, and we now know it through several literary variants and numerous figurative representations. The best-known textual version is found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. During a hunting expedition, the Latin poet tells us, Actaeon, son of the King of Thebes, “wandering through the unfamiliar woods with unsure footsteps”, reaches a clearing, where there is a grotto of extraordinary beauty, and a spring. He arrives there by chance: “for so fate would have it” (“sic illum fata ferebant”). It so happens that at that very moment Artemis is bathing in that spring. Her handmaidens have helped her to undress, and are now pouring water over her body from capacious ewers. The naked nymphs and goddess become aware of the man’s presence and, blushing with shame, begin to utter screams. Artemis, writes Ovid, “stood turning aside a little and cast back her gaze; and though she would fain have had her arrows ready, what she had she took up, the water, and flung it into the young man’s face. And as she poured the avenging drops upon his hair, she spoke these words foreboding his coming doom: ‘Now you are free to tell that you have seen me all unrobed – if you can tell’.” Actaeon is transformed into a stag by the furious goddess: his arms become legs, antlers begin to emerge on his head, and his body is covered with a dappled fur. Actaeon falls prey to terror. He flees, and is amazed at his own speed. He wants to scream, but can only bell, like a deer. Sensing him as prey, his pack of hounds begins to follow him, and they soon block his path and tear him to pieces. Torn apart by his own dogs: that is the horrendous end of Actaeon, guilty – according to Ovid – of having seen Artemis naked, by chance.

The bodies of the gods are sacred; seeing the nude body of a goddess is sacrilege. Again Callimachus, recalling the laws of Kronos: “Whosoever shall behold any of the immortals, when the god himself chooses not, at a heavy price shall he behold”. Seeing, punished as a crime: that is the crucial theme that forms the inspiration for this book.

Read lessSong of Songs (Shìr hasshirìm)

Paperback, 17 x 21 cm, 64 pages, 48 tritone plates - euro 15,00

2023

How beautiful you are, my darling! Oh, how beautiful! Your eyes behind your veil are doves. Your hair is like a flock of goats descending from the hills of Gilead. Your teeth are like a flock of sheep just shorn, coming up from the washing. Each has its twin; not one of them is alone….

Read moreHow beautiful you are, my darling!

Oh, how beautiful!

Your eyes behind your veil are doves.

Your hair is like a flock of goats

descending from the hills of Gilead.

Your teeth are like a flock of sheep just shorn,

coming up from the washing.

Each has its twin;

not one of them is alone.

Your lips are like a scarlet ribbon;

your mouth is lovely.

Cyan Ferns & Blue Dahlias

Hardback, 33 x 44 cm, 96 pages, 84 plates

out of stock

With Atkins’ herbals before us, we now face a typical, and very interesting, question from the years of early photography: how does the advent of a new technology graft itself onto a figurative tradition built up over centuries? The most illuminating instance, first emphasized by Gisèle Freund in the 1930s, is the continuity that linked…

Read moreWith Atkins’ herbals before us, we now face a typical, and very interesting, question from the years of early photography: how does the advent of a new technology graft itself onto a figurative tradition built up over centuries? The most illuminating instance, first emphasized by Gisèle Freund in the 1930s, is the continuity that linked the miniature (a small-format painted portrait) and the carte de visite (a small-format photographic portrait). In this case, the continuity is a truly striking one: the advent of new technology (photography on albumen paper) made accessible to a much wider and less aºuent public a practice – that of the small-format portrait – until then limited to the wealthier classes and aristocrats. However, in other cases, this new technological availability did not have equally linear consequences. […] The disclosure of the first photographic processes, such as Talbot’s photogenic drawing and Herschel’s cyanotype, o¤ered new horizons for the old herbarium tradition. But the new technology, as we have said, did not allow for results that might provide valid contributions to scientific research. A new genre was born – a distinct genre with independent functions and language.

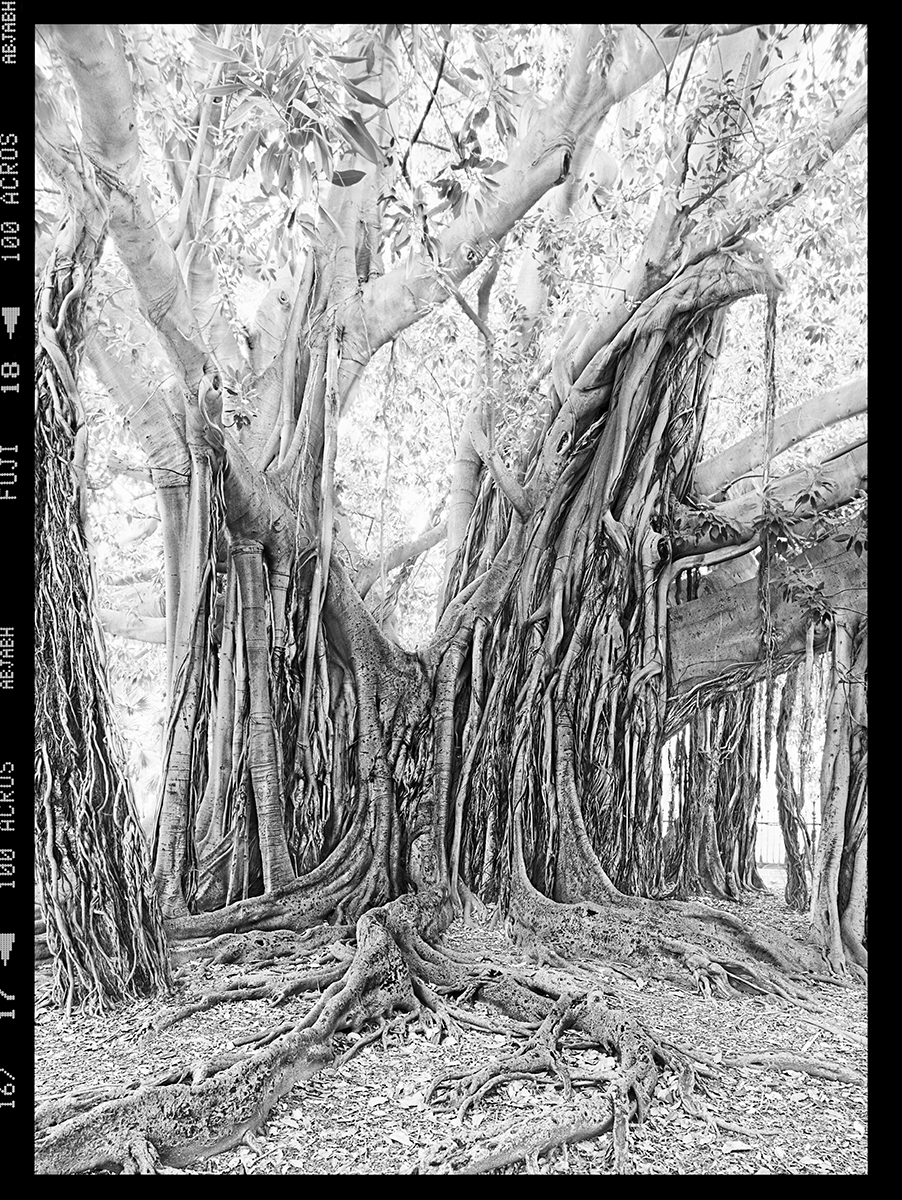

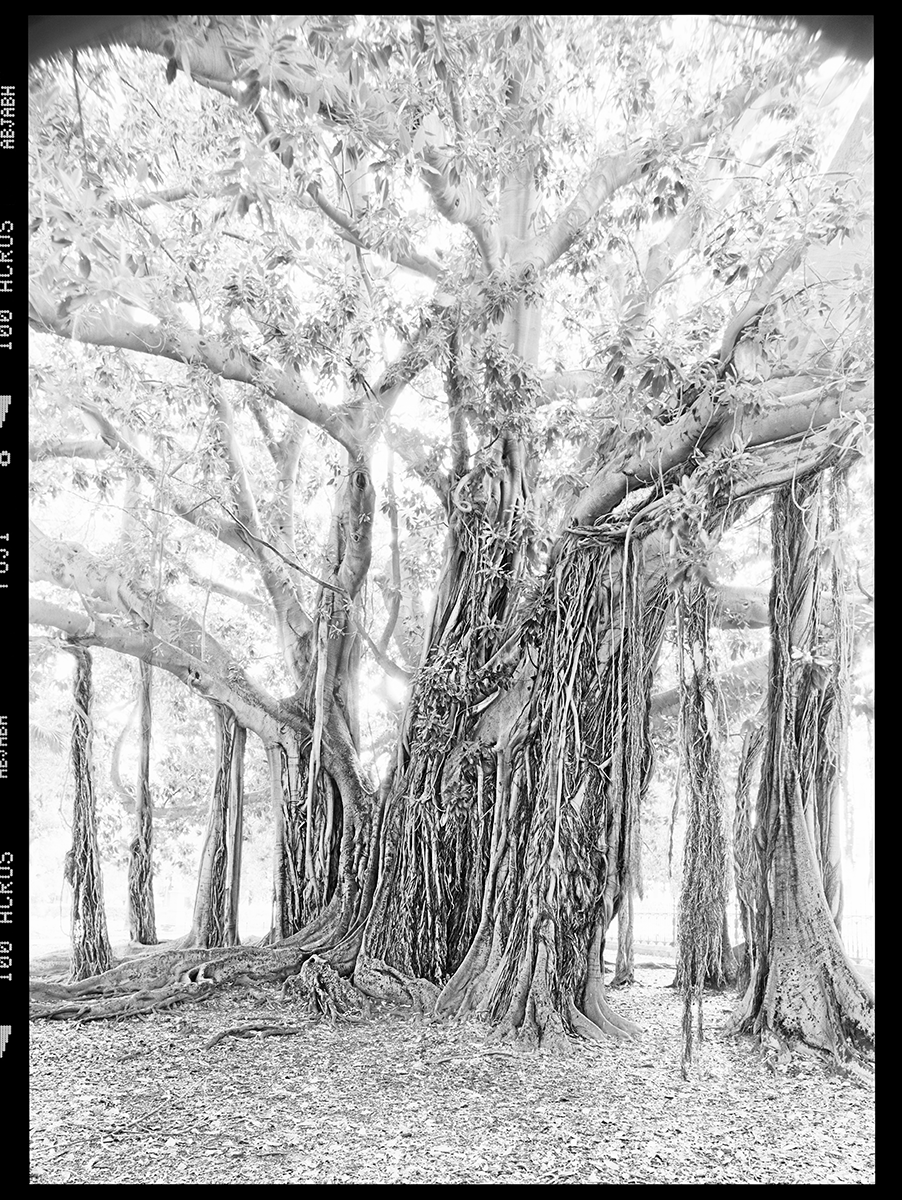

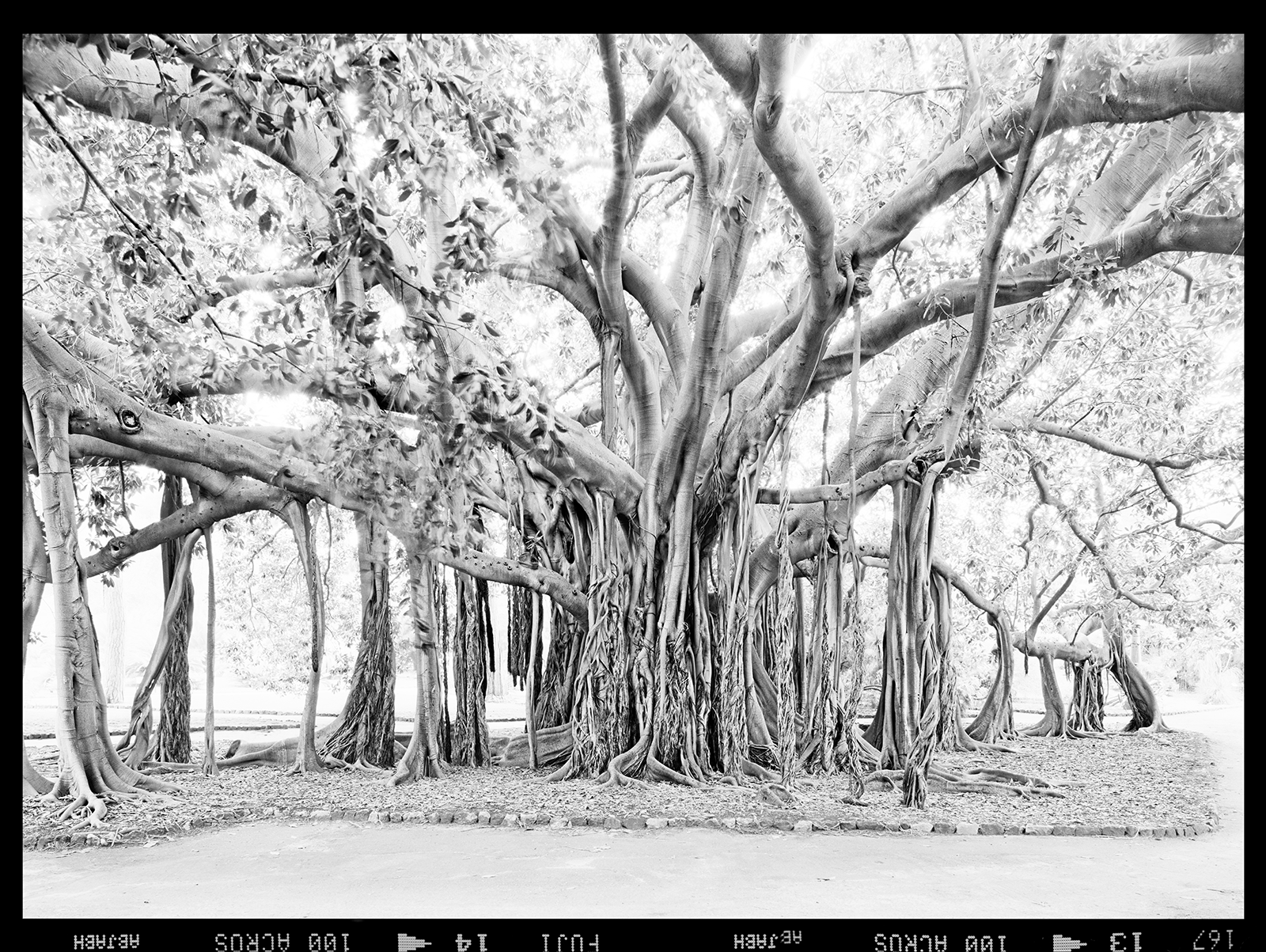

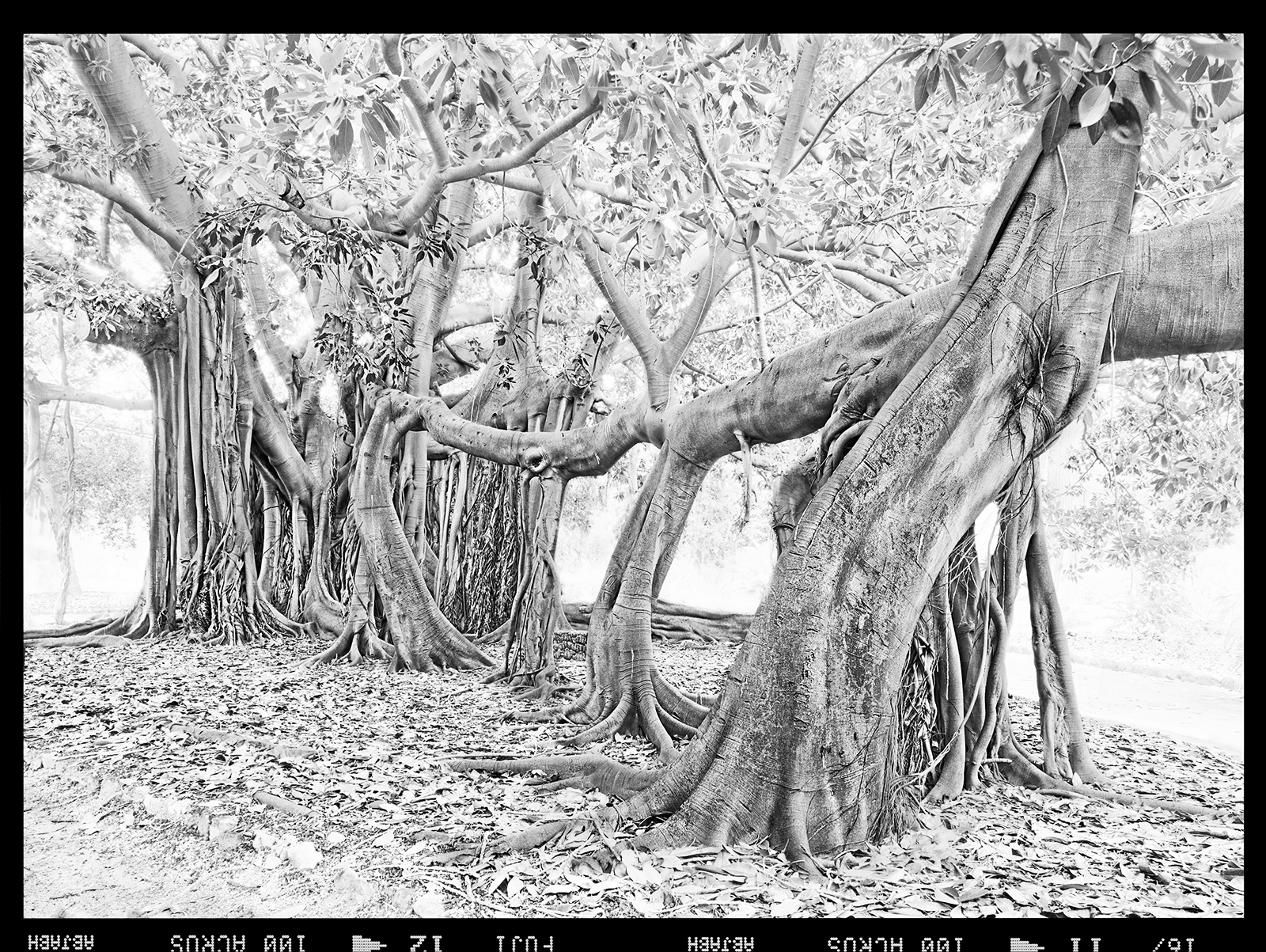

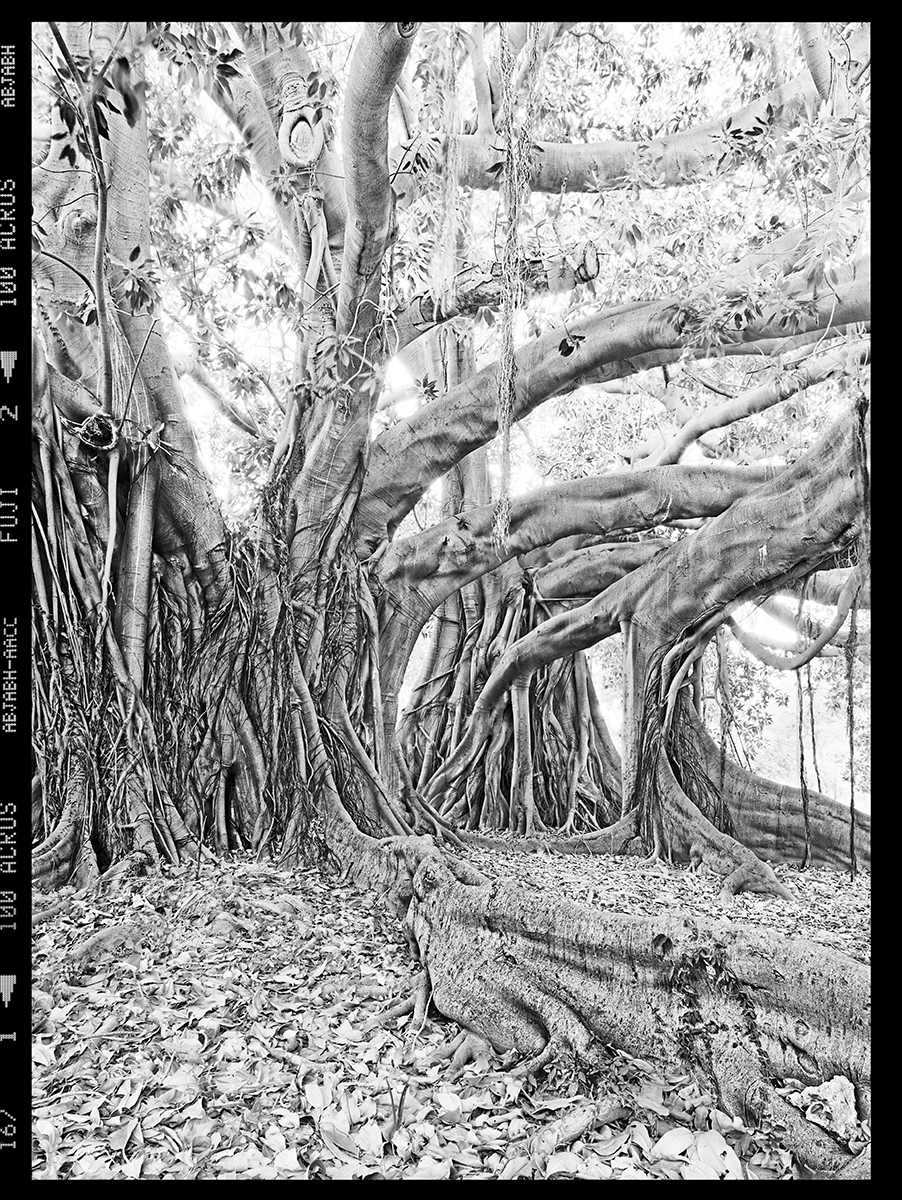

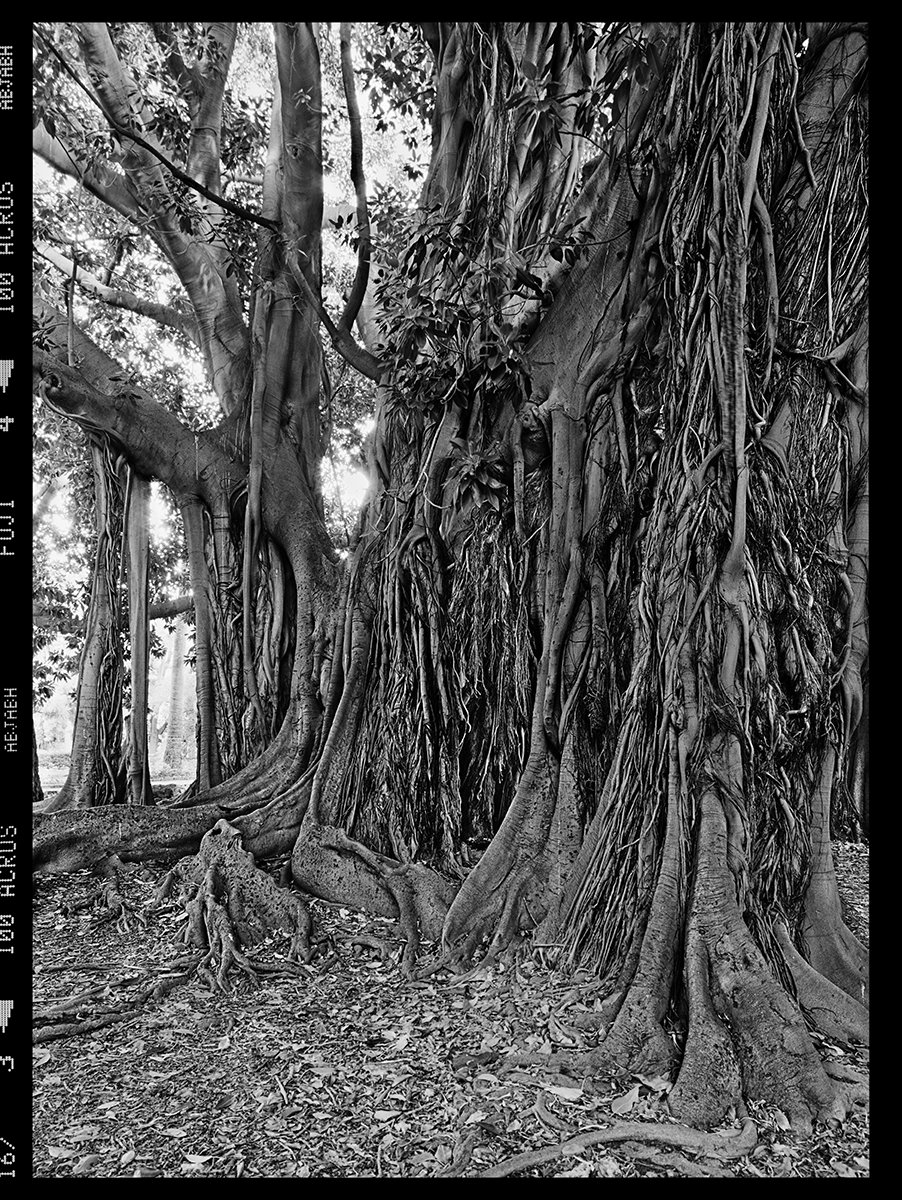

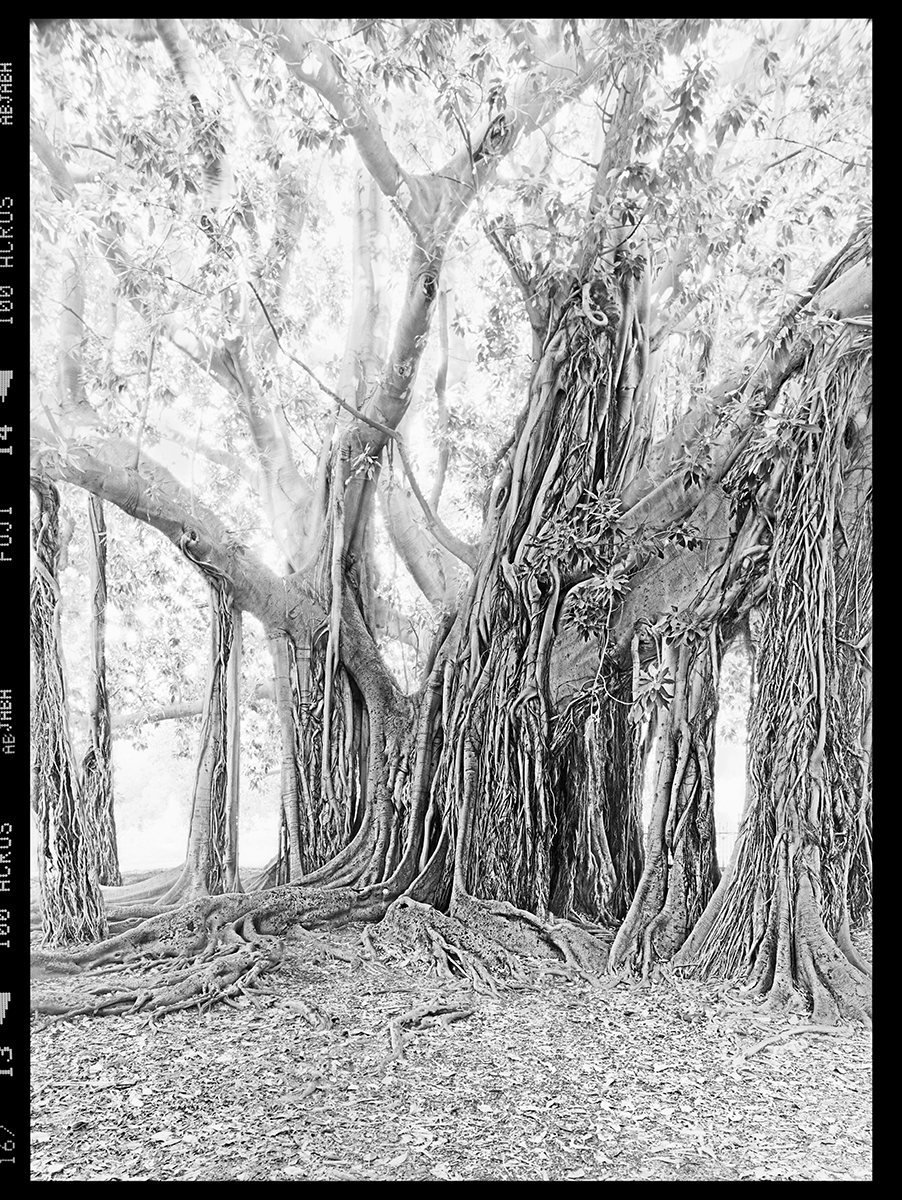

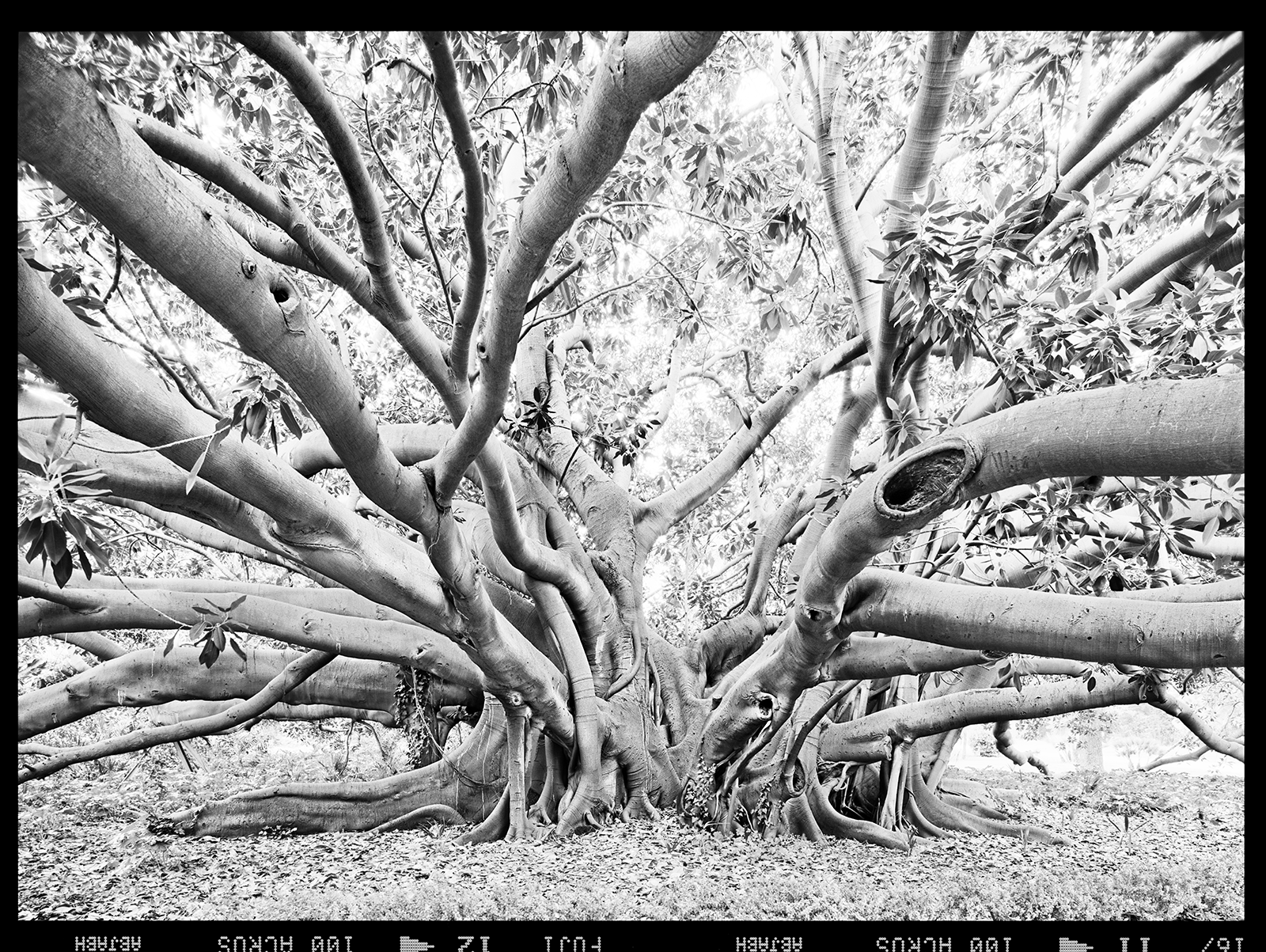

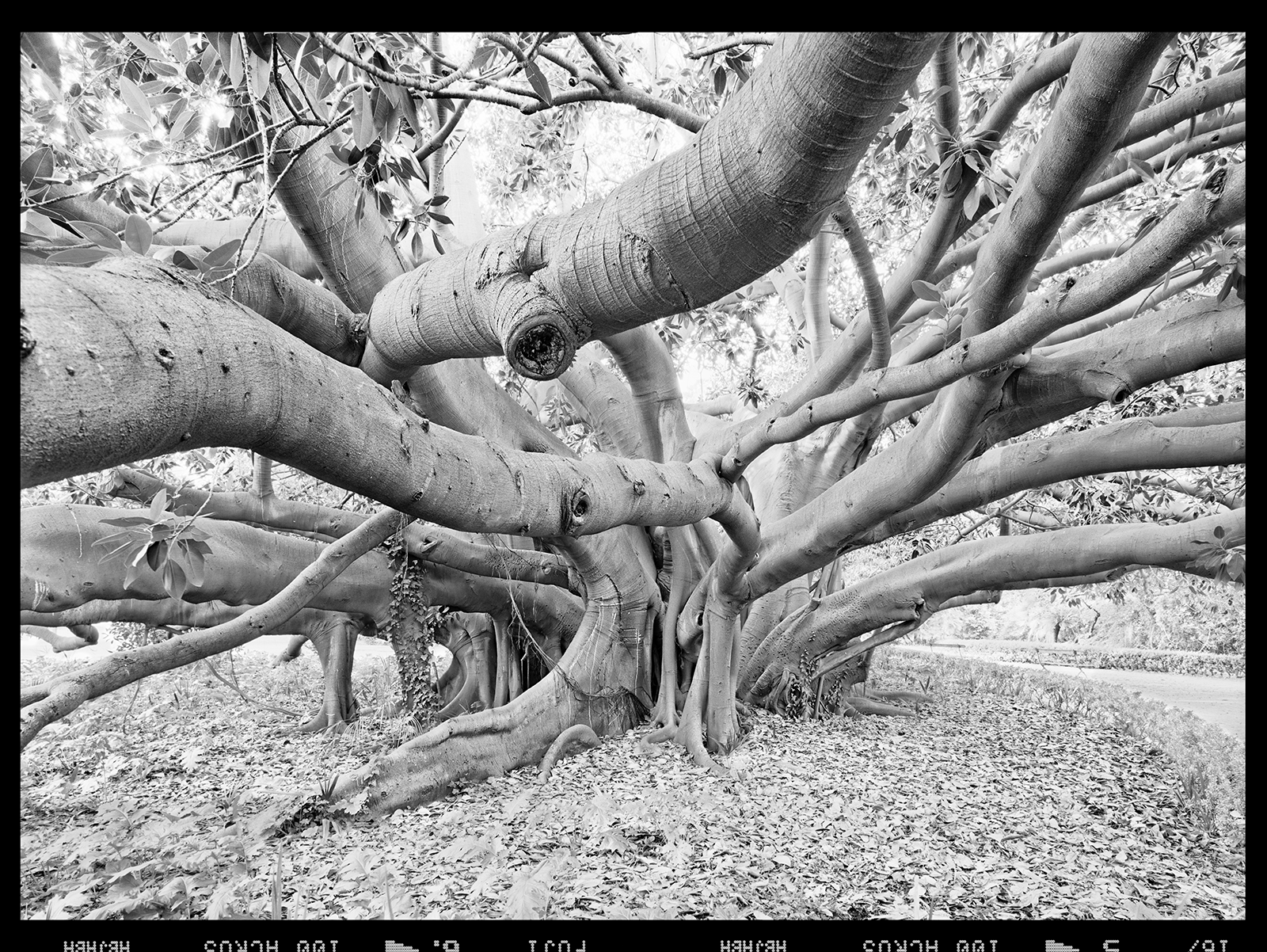

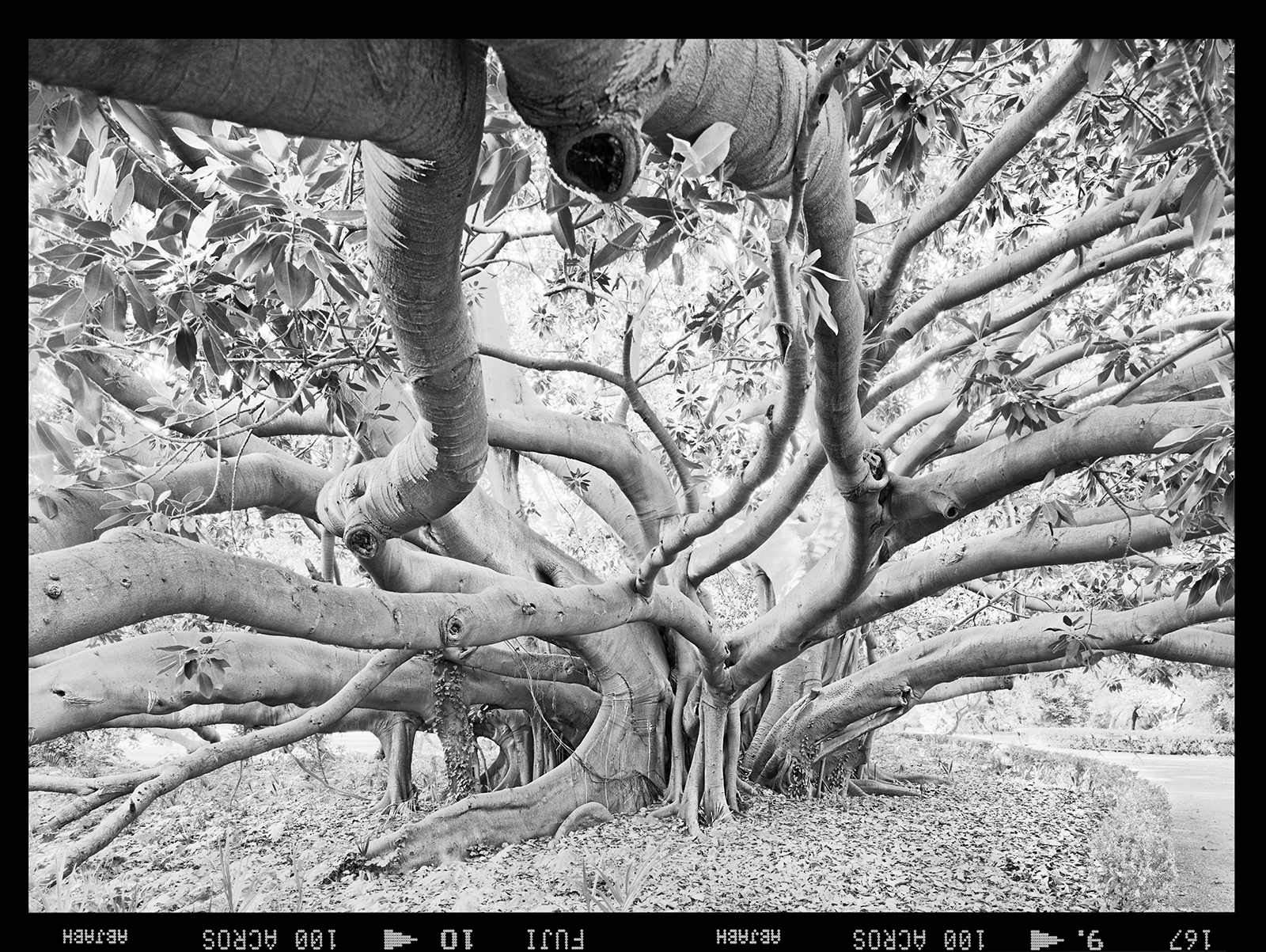

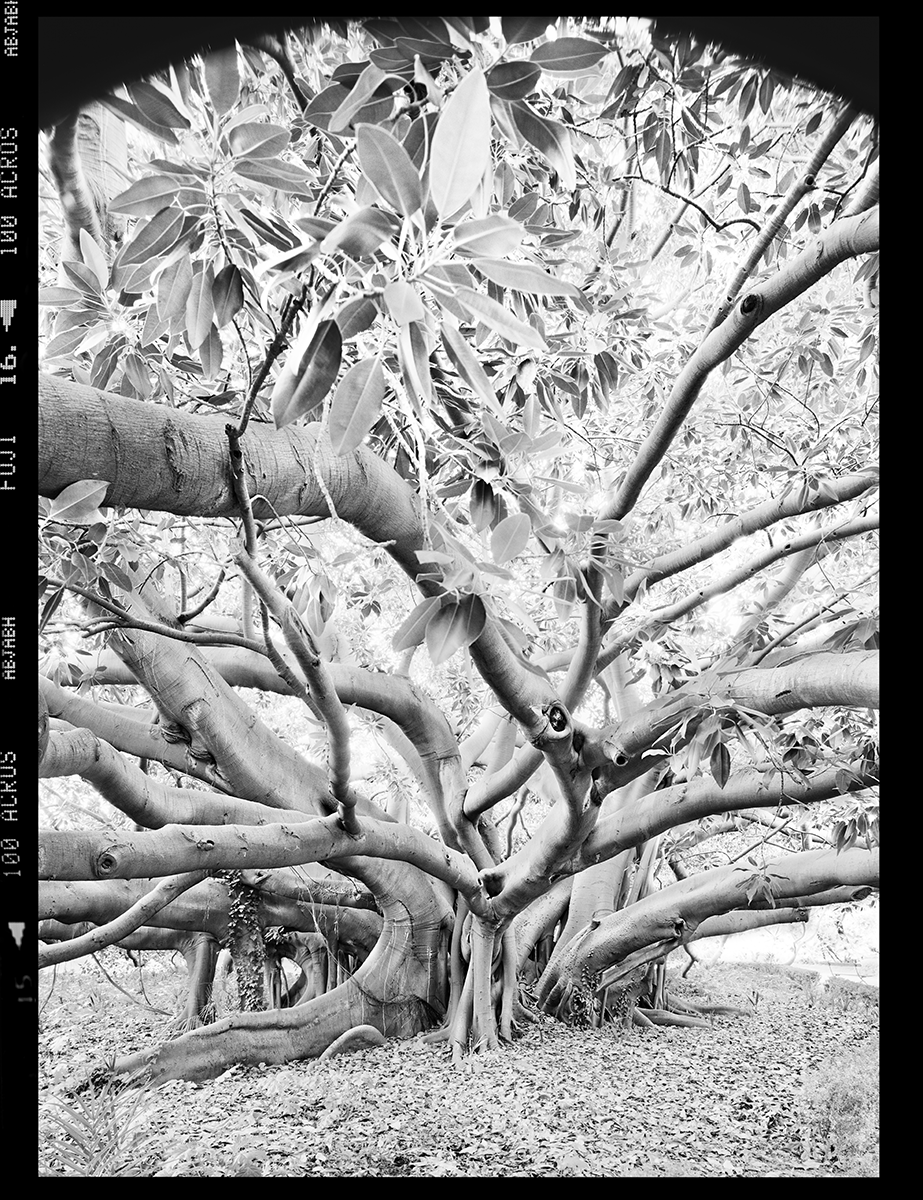

Read lessThe Tale of The Banyan Tree

Hardback, 33 x 44 cm, 64 pages, 28 plates

out of stock

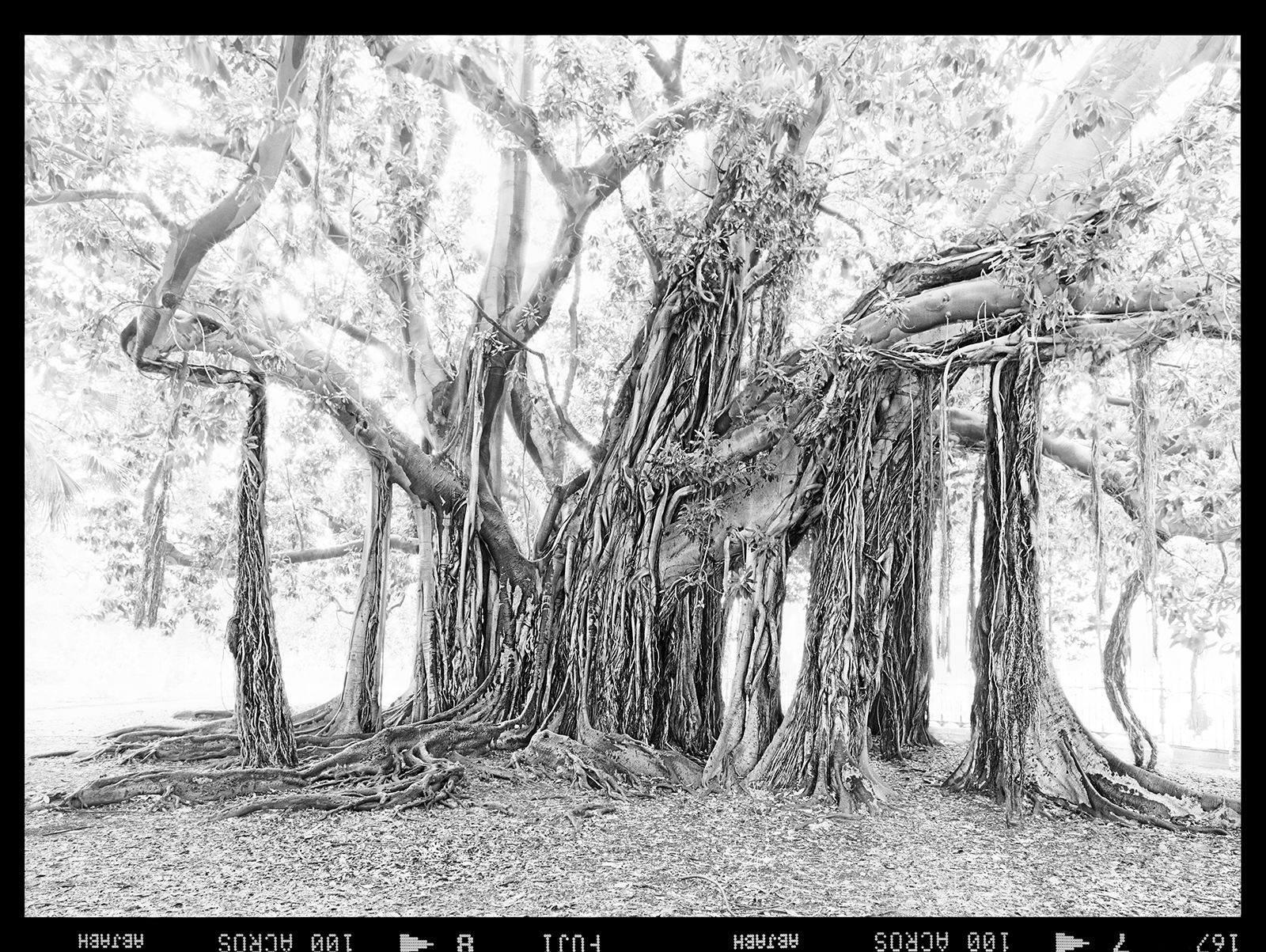

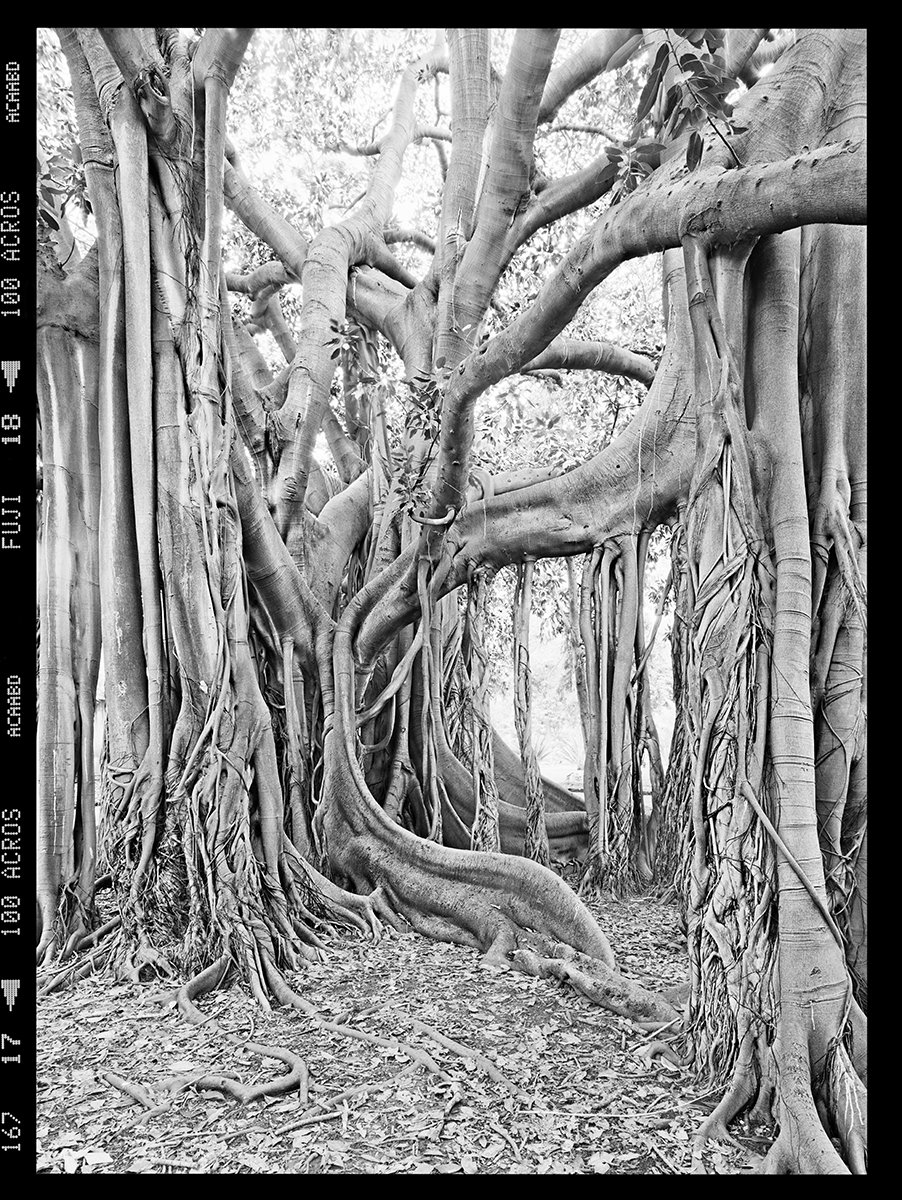

In India, a huge tree, with large, heart-shaped leaves, grew near the temple of Mahabodhi. It was an old specimen of Ficus religiosa; in Sanskrit, its name — Ashwattha — means ‘that which changes’. According to legends, under that tree Siddharta Gautama sat a long time in meditation, until he got the Bodhi, that is the awakening. For this reason,…

Read moreIn India, a huge tree, with large, heart-shaped leaves, grew near the temple of Mahabodhi. It was an old specimen of Ficus religiosa; in Sanskrit, its name — Ashwattha — means ‘that which changes’. According to legends, under that tree Siddharta Gautama sat a long time in meditation, until he got the Bodhi, that is the awakening. For this reason, that banyan tree is known as the Sri Maha Bodhi, or the Bodhi Tree. Still today, in that place there is a great banyan tree, which is said to descend from that under which the Buddha was enlightened. It is considered a sacred tree, and therefore the name of Ficus religiosa was given to its species. Believers of many religions go on pilgrimage there. Gentle and mighty, generous in affording a shelter to wayfarers caught short by rainstorms or exhausted by the summer heat, its name recurs often in old sacred Indian books and in Buddhist legends. In the Chandogya Upanisad, Svetaketu learns from his father how such a gigantic tree can come from a tiny seed, and how in that Nothing the essence of every thing is hidden. Another species — the Ficus benghalensis — in Sanskrit is called Nyagrodha, which means ‘that which grows downwards’. What makes these trees so monumental and moving is the framework of aerial roots, which, reaching the ground, become ancillary trunks, and help to support the weight of the foliage. If one agrees that these trees could have a symbolical value, and that their marvellous shapes could be a teaching to men, then one will understand how the issue that the banyan tree raises is that of rooting. It is not just a matter of the strength of the roots, but rather of the will to connect the top with the bottom. The strength of the result depends on this will. Leaves and roots depend on each other: without the latter, the former would die, and vice versa. It is essential that there is an effective connection so that this mutual function can take place. Without a good link, sap could not rise to the top, and, conversely, the energy synthesized by the leaves could not come back to the ground. For these reasons, banyan trees recur in many religions’ symbology, with the name of Tree of the World, with the celestial specularly superimposed to the mundane. It reminds wayfarers that the Top and the Bottom belong to each other.

Read lessFotosfer

2/2022

Upon the Primacy of the Greeks

Xanthi, Thracian Arts and Traditions Foundation

December 18th, 2019 - January 31st, 2020

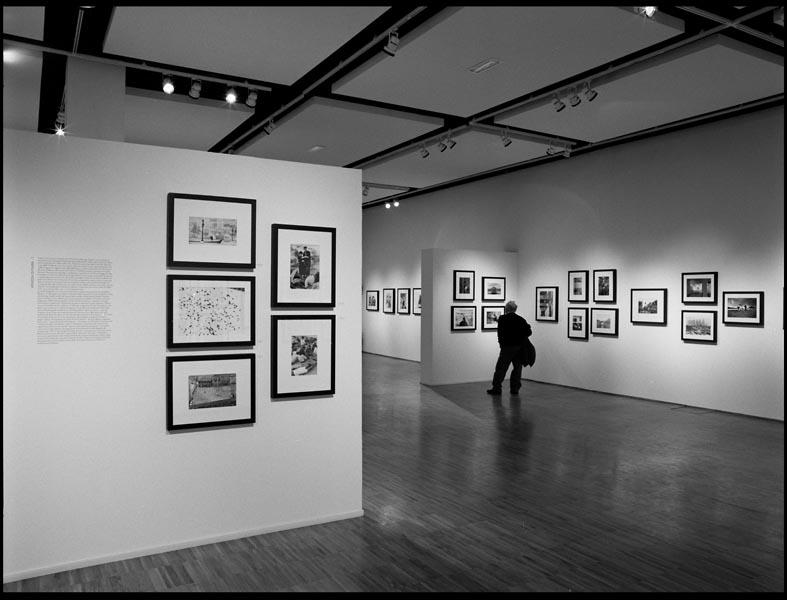

On Light

Rosphoto - State Museum of Photography, Sankt Petersburg (Russian Federation)

July 9th – August 31st 2015

Greek myths, ancient tales, archaeological sites of the Mediterranean basin and the Midlle East, sacred books from the Books of Veda to the Bible, and the never ending work of interpretation are the themes upon which Paolo Morello’s photographic work is grounded. Rosphoto is proud to present Upon Light, a solo exhibition of the Italian…

Read moreGreek myths, ancient tales, archaeological sites of the Mediterranean basin and the Midlle East, sacred books from the Books of Veda to the Bible, and the never ending work of interpretation are the themes upon which Paolo Morello’s photographic work is grounded. Rosphoto is proud to present Upon Light, a solo exhibition of the Italian photographers, which gathers together a wide selection of works realized over the past ten years.

The works on display come from some of the mayor series by the photographer. In the series entitled “In the Beginning” some myths of creation are compared. Going through Hesiod’s Theogony and the book of Genesis, Morello reflects upon some specific motifs, among them the “chaos” – the primordial abyss –, the Eden – the paradisiacal garden –, the life which takes shape from the inchoate mud, the divine breath – the “alitus” –, and finally the coming to the surface of the Earth from the depths of the Ocean. “All of these themes have much to do with photography” – the photographer says –. “Cosmogonic myths were conceived as metaphors of the progressive widening of the consciousness. Photography too is an exercise of progressive understanding and appropriation within the boundaries of the knowledge. In sanskrit, the verbs to see and to know have the same root: vidya”.

The series entitled “Aphrodite’s Nostalgia” takes as well its origins from an ancient myth, that of the goddess of love, and of her symbol, the shell. The shell was neither a symbol of her beauty, nor of her femininity, rather of her birth. To what extent are we aware of our deepest memories, such as those linked to our origin and our birth? “Images have an extraordinary power to awaken our most repressed and obliterated memories – Morello explains —, and with this aim the works included in this section were conceived. When we look at a picture, we use an area of our brain which is much older than that which we use to speak. Primitive men learned to recognize images millions of years before they started to articulate words. This is the reason why some photographs have such an immediate effect in producing emotional reactions upon the watchers. When we face a shell, or a nude feminine body which alludes to birth giving, a bell rings in the most secluded and irrational part of our mind”.

The third series is devoted to “The Myth of Petra”, the ancient Nabatean capital, now in Jordan. Despite the worldwide fame of its rose-reddish sandstone, Morello decided to photograph its tombs and monuments in black and white in order to keep off the way it is usually represented in touristic postcards. The uniqueness of that site is primarily due to the relationship between nature, rocks and architecture. The local sandstone is very frail, and that made possible to the Nabateans to easily carve such huge buildings in the Ist century BC. At the same time, the frailty of the stone makes these buildings subject to an incessant deterioration. In a kind of circular way, the same mountains which were carved by men and then became a town are now going back to sand. The architecture is vanishing under the action of the rain and the wind. What we see now are just the remaining traces of a lost splendour, and for sure this is not what they will see in a century.

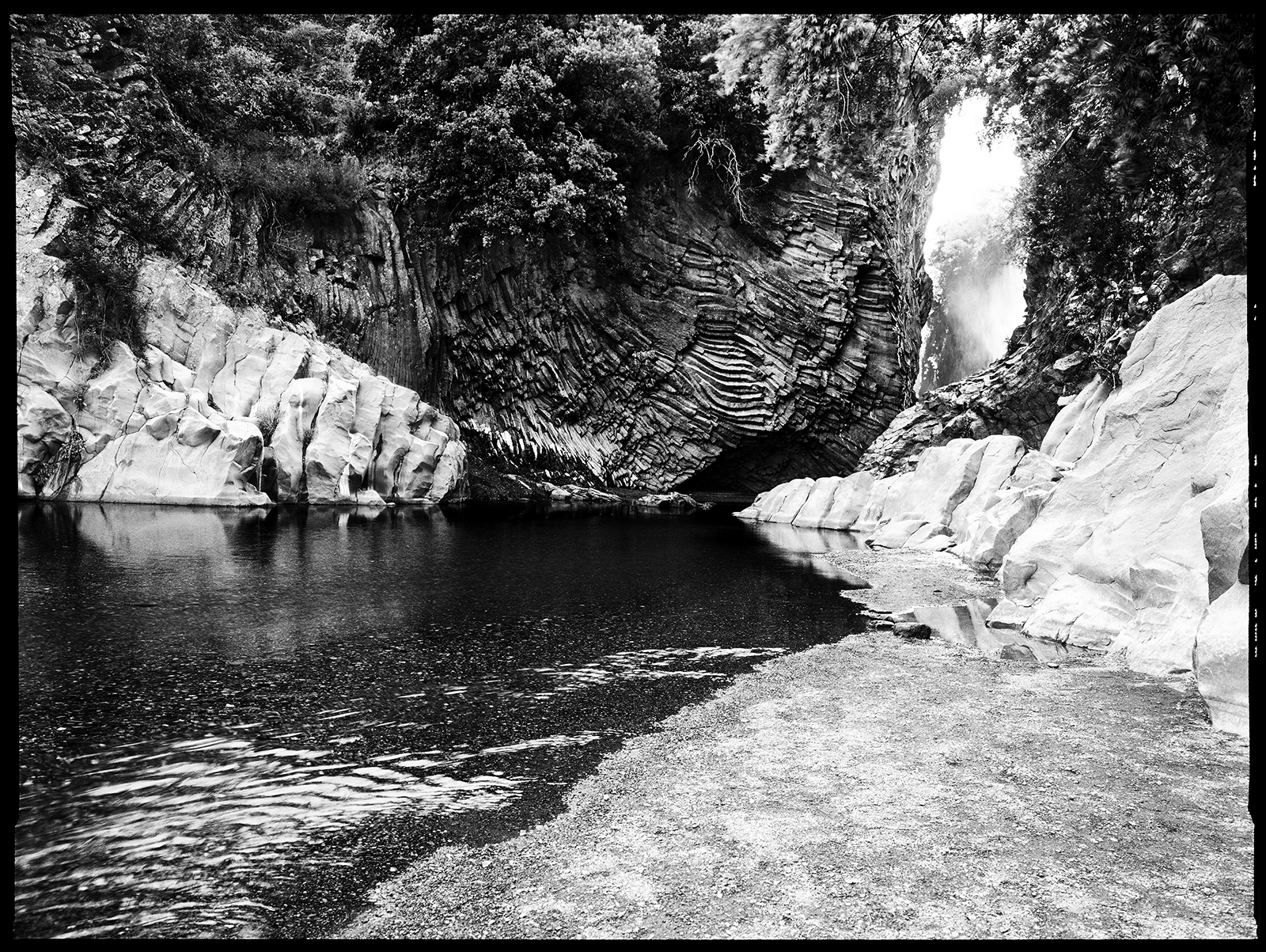

Some landscapes in the show are part of “A Journey to Sicily”, which, in the photographer’s view, is still the land inhabited by the ancient Greeks, where many myths took place. It is the land of the Cyclops, where Odysseus blinded the giant Polyphemus during his journey back home to Ithaca from the Trojan War. Homer set in Sicily also the scaring Laestrygonians, a people of cannibals who lived with no laws and no liking for labour. Many ancient myths show a great modernity and some seem to allude to present circumstances.

The “Tale of the Banyan Tree” was originally released in 2007 in a quite different edition, but their breathtaking beauty well deserved a new series of photographs. In Sanskrit, the Banyan tree is called Nyagrodha, which means “that which grows downwards”. What makes it so monumental and moving is the framework of aerial roots, which, reaching the ground, become ancillary trunks, and help to support the weight of the foliage. If one consider the symbolical value of its rooting, one will discover in it the will to connect the top with the bottom. The strength of the result depends on this will. Leaves and roots depend on each other: without the latter, the former would die, and vice versa. It is essential that there is an effective connection so that this mutual function can take place. Without a good link, sap could not rise to the top, and, conversely, the energy synthesized by the leaves could not come back to the ground. Banyan Trees are considered sacred trees in many religions. They reminds wayfarers that the Top and the Bottom belong to each other.

Read less

Italian Realism. Masterpieces from the Collection of Paolo Morello

Moscow, Big Manezh

March, 18th - April, 24th 2011

La fotografia in Italia. Capolavori della fotografia italiana dalla collezione Paolo Morello

Milano, Fondazione Forma

February, 12th - June, 2th 2010

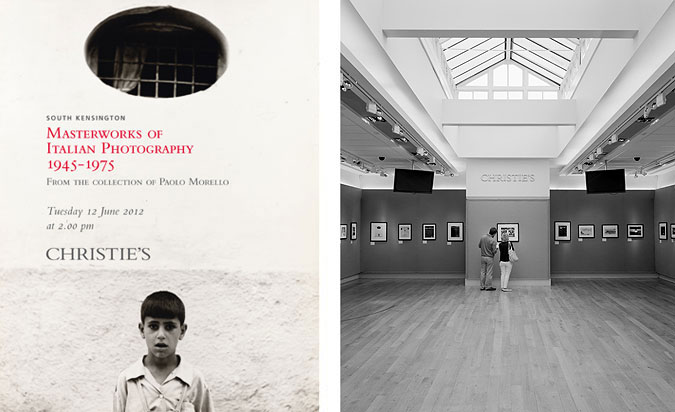

Masterworks of Italian Photography from the Collection of Paolo Morello

London, Christie’s South Kensington

12th June, 2012

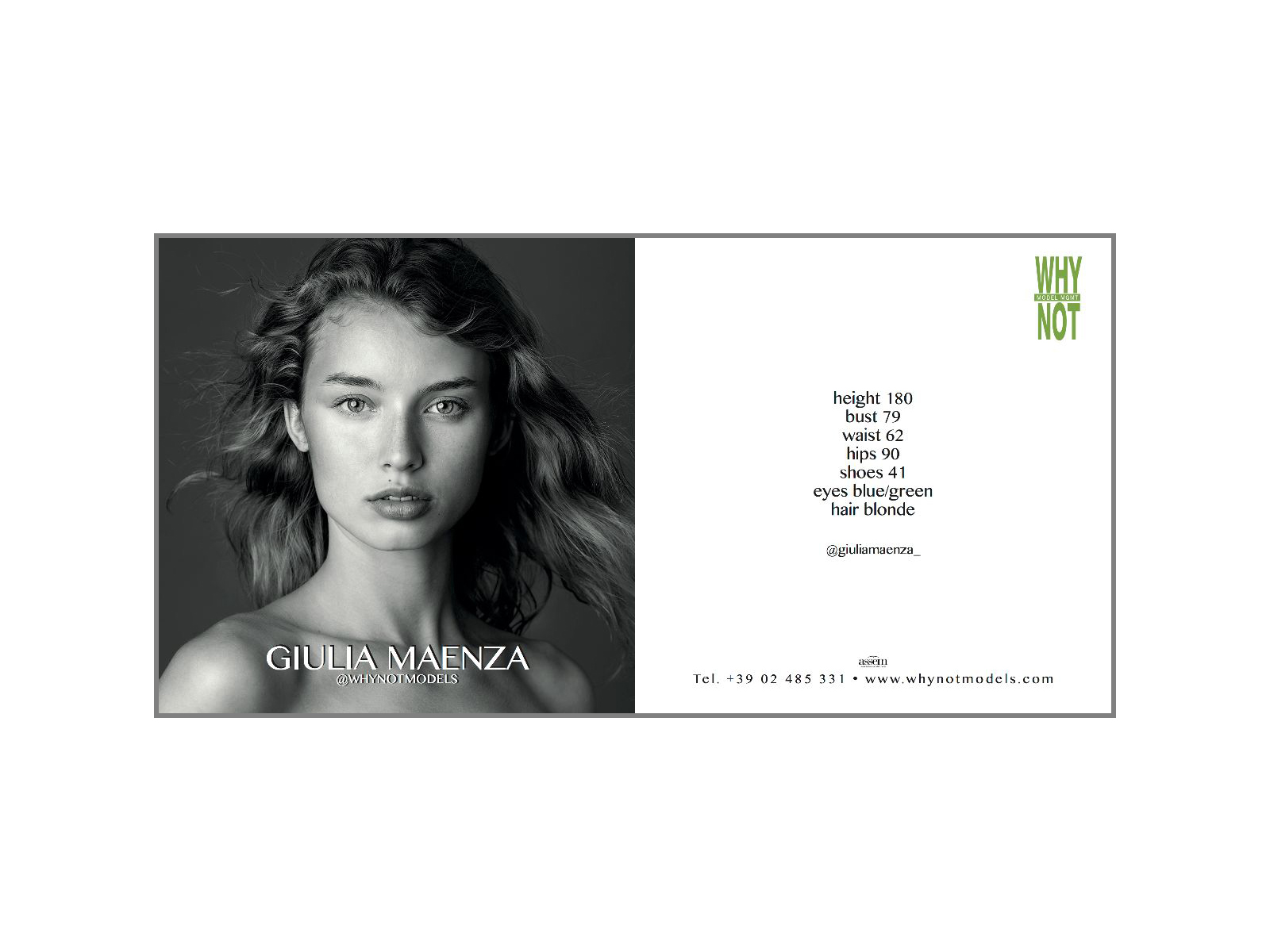

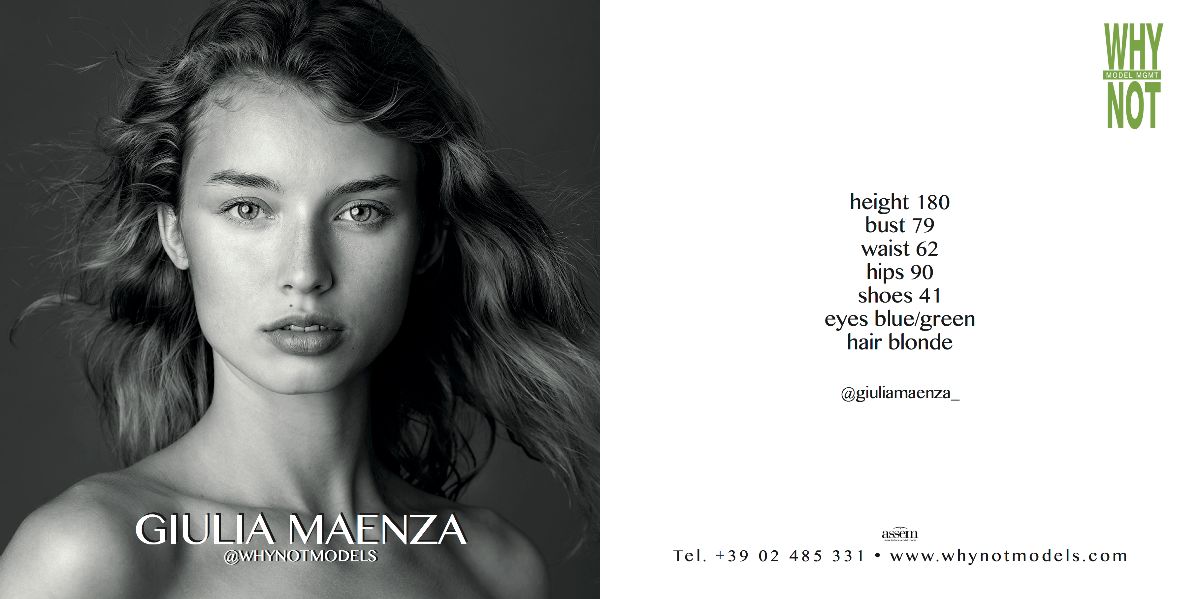

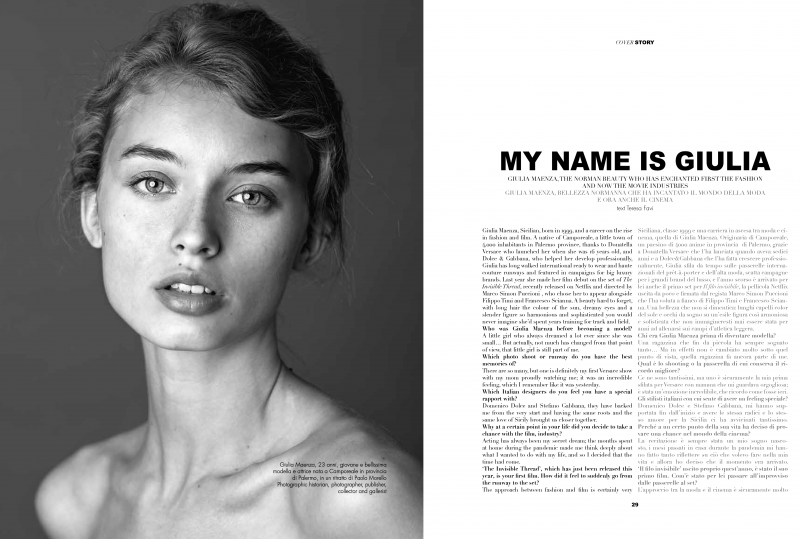

Ravishing Giulia

2018

A portrait is not a representation of an individual in his objective reality, or, as we often read, the ‘revelation of his true, most intimate essence’. Photography does not capture the ‘essence’ of an individual, it does not ‘steal his soul’, it does not represent in the ‘most authentic way’ a personality because the Ego…

Read moreA portrait is not a representation of an individual in his objective reality, or, as we often read, the ‘revelation of his true, most intimate essence’. Photography does not capture the ‘essence’ of an individual, it does not ‘steal his soul’, it does not represent in the ‘most authentic way’ a personality because the Ego is, by definition, multiple. There is nothing less identical to itself than identity. For these reasons, it would be completely erroneous to apply the irreconcilable dichotomy between being and appearing, or between εἶδος and εἴδωλον, to the understanding of the relationship of circu- larity, of mutual e¤ectuality, which links the image to identity. To put it in Jacques Lacan’s words, image and identity never cease to constitute each other.

Read lessHelen in the Maze

Palermo, Museum of Palazzo Branciforte

November 12th, 2021 - January 16th 2022

RaiDue, January 6th, 2022, https://www.rainews.it/rubriche/tg2italia?fbclid=IwAR0Ye6xvFjDEPYdJ4D3MrncWX (from minute 46) RaiTre, February 5th, 2022: https://www.rainews.it/tgr/rubriche/bellitalia (from minute 13.40)

Read moreRaiDue, January 6th, 2022, https://www.rainews.it/rubriche/tg2italia?fbclid=IwAR0Ye6xvFjDEPYdJ4D3MrncWX (from minute 46)

RaiTre, February 5th, 2022: https://www.rainews.it/tgr/rubriche/bellitalia (from minute 13.40)

HELEN IN THE MAZE AT VILLA IGIEA, A ROCCO FORTE HOTEL, PALERMO

SICILIA THE LAND OF SUN

May 2022

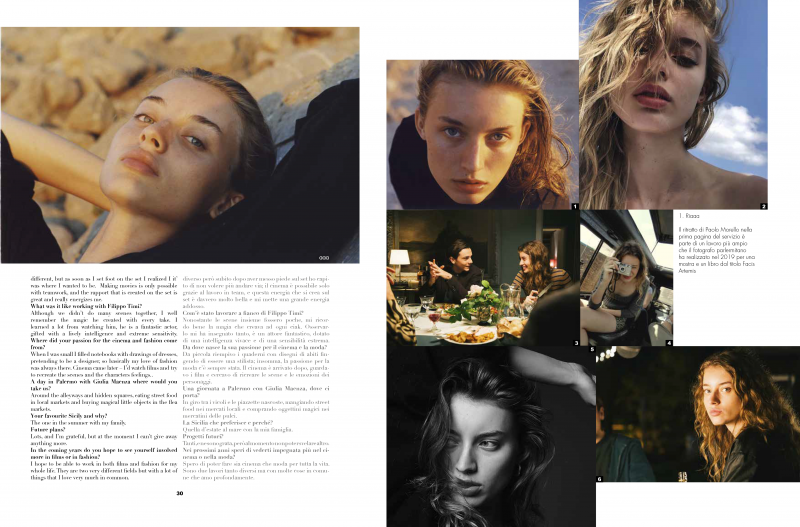

Beautiful Giulia Maenza in a portrait of mine on the cover of Sicilia the Land of Sun, May 2022

Read moreBeautiful Giulia Maenza in a portrait of mine on the cover of Sicilia the Land of Sun, May 2022

Read lessAriadne at the Turkish Bath

2014-2020

Tempus erat, vitrea quo primum terra pruina spargitur et tectae fronde queruntur aves; incertum vigilans ac somno languida movi Thesea prensuras semisupina manus: nullus erat. Referoque manus iterumque retempto perque torum moveo bracchia: nullus erat. Ovidio, Heroides, X. Ariadne Theseo

Read moreTempus erat, vitrea quo primum terra pruina

spargitur et tectae fronde queruntur aves;

incertum vigilans ac somno languida movi

Thesea prensuras semisupina manus:

nullus erat. Referoque manus iterumque retempto

perque torum moveo bracchia: nullus erat.

Ovidio, Heroides, X. Ariadne Theseo

In the Beginning

2007

«Thus, in the beginning was chaos», writes Hesiod in the Theogony. For a Greek from the eighth century BC, chaos meant abyss: the chasm yawning from the surface down to the depths of Origin. Chaos, the primordial void, is first and foremost an absence: it is an absence of matter and form, but it is…

Read more«Thus, in the beginning was chaos», writes Hesiod in the Theogony. For a Greek from the eighth century BC, chaos meant abyss: the chasm yawning from the surface down to the depths of Origin. Chaos, the primordial void, is first and foremost an absence: it is an absence of matter and form, but it is also darkness, an absence of light. Yet it is capable of creating its opposites. Even as a figure of void, it can transform itself into a symbol of overflowing plenitude. Just as the Earth falls away at the mouths of volcanoes, from these same chasms comes forth magma, and it is from this outpouring that the Earth is formed. Moreover, myths of creation can be read as a representation of the emergence of consciousness. Behind the image of the Earth rising up from the depths of the ocean, or of Man taking form out of clay, Man’s becoming aware of himself, of the cosmos, and of creation, is revealed. Even the gradual appropriation of thick undergrowth, the retrieval of land from a tangle of plants, and unearthing, ploughing, and cultivation, are all representations of the arduous wearing away by the consciousness of all that is instinctual, compulsive, and irrational – or rather natural – in the darkest recesses of the unconscious psyche. Every cosmogony thus represents an e¤ort to widen the boundaries of the field of consciousness. Exterior reality is created and exists as it comes to the surface of awareness. The crucial theme of these photographs is therefore consciousness. Photography helps to show the dual nature of art better than any other type of representation. On the one hand, it produces new myths. It nourishes the universe of the imaginal, offering new material for analysis. On the other hand, photography itself constitutes an instrument of analysis. It compels us to reflect upon the contingent reality which appears before the lens, but also forces the photographer to continually question the meaning of seeing. Every new photograph helps us to extend our awareness of the world but also forces us to become conscious of our being-as-capable of consciousness.

Read lessVanishing Point

2018

Upon the Primacy of the Greeks

Athens, Epigraphic Museum

September 21st - October 26th 2017

Petrodvorec, Marly Pavillion

August 2014